Authoritarian Expansion and the Power of Democratic Resilience

TAIPEI, TAIWAN – June 23, 2019: Protesters hold placards with messages that read “reject red

media” and “safeguard the nation’s democracy” during a rally against pro-China media in front of the Presidential Office building in Taipei. Photo credit: HSU TSUNHSU/AFP via Getty Images.

The Chinese government’s media influence efforts have increased since 2019 in most of the 30 countries under study, but democratic pushback has often curbed their impact.

Key Findings

- The Chinese government has expanded its global media footprint. The intensity of Beijing’s media influence efforts was designated as High or Very High in 16 of the 30 countries examined in this study, which covers the period from January 2019 to December 2021. In 18 of the countries, the Chinese regime’s efforts increased over the course of those three years.

- The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its proxies are using more sophisticated and coercive tactics to shape media narratives and suppress critical reporting. Mass distribution of Beijing-backed content via mainstream media, harassment and intimidation of outlets that publish news or opinions disfavored by the Chinese government, and the use of cyberbullying, fake social media accounts, and targeted disinformation campaigns are among the tactics that have been employed more widely since 2019.

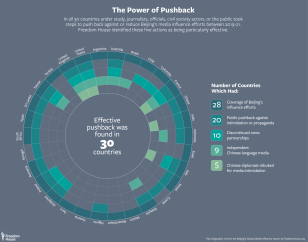

- The success of Beijing’s efforts is often curtailed by independent media, civil society activity, and local laws protecting press freedom. Journalists, scholars, and civil society groups in all 30 countries responded to influence campaigns in ways that increased transparency, ensured diverse coverage, and enhanced local expertise on China. Laws governing freedom of information or media ownership, which are present in many democracies, helped to ensure transparency and insulate media ecosystems from CCP influence.

- Inadequate government responses leave countries vulnerable or exacerbate the problem. Declines in press freedom and gaps in media regulations have reduced democratic resilience and created greater opportunities for future CCP media influence. In 23 countries, political leaders launched attacks on domestic media or exploited legitimate concerns about CCP influence to impose arbitrary restrictions, target critical outlets, or fuel xenophobic sentiment.

- Democracies’ ability to counter CCP media influence is alarmingly uneven. Only half of the countries examined in this study achieved a rating of Resilient, while the remaining half were designated as Vulnerable. Taiwan faced the most intense CCP influence efforts, but it also mounted the strongest response, followed in both respects by the United States. Nigeria was deemed the most vulnerable to Beijing’s media influence campaigns.

- Long-term democratic resilience will require a coordinated response. Governments, media outlets, civil society, and technology firms all have a role to play in enhancing democratic resilience in the face of increasingly aggressive CCP influence efforts. Building up independent, in-country expertise on China, supporting investigative journalism, improving transparency on media ownership and disinformation campaigns, and shoring up underlying protections for press freedom are all essential components of an effective response strategy. Governments should resist heavy-handed actions that limit access to information or otherwise conflict with human rights principles, instead forging partnerships with civil society and the media to ensure that all legislative and policy responses strengthen rather than weaken democratic institutions.

Authoritarian Expansion and the Power of Democratic Resilience

“Wherever the readers are, wherever the viewers are, that is where propaganda reports must extend their tentacles.” —Xi Jinping, 2016

“It may be subtle, some of these tricks are geared toward coaxing you to be soft on them [Chinese state-affiliated actors]. As for stopping, they can’t stop me from writing.” — Ghanaian journalist who wished to remain anonymous, 2021

The Chinese government, under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, is accelerating a massive campaign to influence media outlets and news consumers around the world. While some aspects of this effort use the tools of traditional public diplomacy, many others are covert, coercive, and potentially corrupt. A growing number of countries have demonstrated considerable resistance in recent years, but Beijing’s tactics are simultaneously becoming more sophisticated, more aggressive, and harder to detect.

The regime’s investment has already achieved some results, establishing new routes through which Chinese state media content can reach vast audiences, incentivizing self-censorship on topics disfavored by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and co-opting government officials and media owners in some countries to assist in spreading propaganda narratives or suppressing critical coverage. Beijing’s actions also have long-term implications, particularly as it gains leverage over key portions of the information infrastructure in many settings. The possible future impact of these developments should not be underestimated.

The Chinese government, under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, is accelerating a massive campaign to influence media outlets and news consumers around the world.

Moreover, the experience of countries including Taiwan, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia point toward a recent turn to more aggressive, confrontational, or surreptitious tactics as milder influence efforts fail to achieve the desired results. This trend is likely to expand to additional countries in the coming years. More countries—and their researchers, journalists, and policymakers—should expect to encounter a rise in diplomatic intimidation, cyberbullying, manipulation by hired influencers on social media, and targeted disinformation campaigns designed to sow confusion about the CCP and their own societies. The Chinese regime and its proxies have shown that they have no qualms about deploying economic pressure to neutralize and suppress unfavorable coverage. As more governments and media owners face financial trouble, the likelihood increases that economic pressure from Beijing will be used, implicitly or explicitly, to reduce critical debate and reporting—not only on China’s domestic or geopolitical concerns, but also on its bilateral engagement with other countries.

More from BGMI

gettyimages-11376750153fa1.jpg?h=06f4bf3b&itok=o0GnfmNW)

Recommendations

Recommendations for media, governments, civil society, donors, and tech companies.

Country Reports

Scores and findings from the 30 countries surveyed in the BGMI report.

%20gettyimages-1300308201%20(1)fa64.jpg?h=d68b7e6b&itok=2qynGrsl)

Methodology

More on the research, country selection, and scoring for Freedom House’s BGMI report.

Democracies are far from helpless in the face of the CCP’s influence efforts. In many countries, journalists and civil society groups have led the way by ensuring diversity of coverage, exposing coercive behavior and disinformation campaigns, and instilling both vigilance and resilience in a new generation of media workers, researchers, and news consumers. Meanwhile, some democratic governments are pursuing initiatives to increase transparency, improve coordination among relevant agencies, punish coercive actions by foreign officials, and spur public debate about the need for safeguards amid increased trade and investment with China. These measures will address Beijing’s encroachments while strengthening democratic institutions and independent media against other domestic and international threats. Such steps may require considerable political will—and a reversal of recent domestic pressure on media freedom in many countries. But allowing the CCP’s authoritarian media influence campaign to expand unchecked would carry its own costs for freedom of expression, access to uncensored information about China, and democratic governance in general.

For this report, Freedom House examined Beijing’s media influence efforts across 30 countries, all of which were rated Free or Partly Free in Freedom in the World during the 2019–21 coverage period. Of this group, 18 countries encountered expanded media influence efforts. In 16 of the 30, the intensity of CCP influence efforts was found to be High or Very High, while 10 countries faced a Notable level and only 4 countries faced a Low level. At the same time, all 30 countries demonstrated at least one incident of active pushback by policymakers, news outlets, civic groups, or social media users that reduced the impact of Beijing’s activities. Indeed, based on available data, public opinion toward China or the Chinese government has declined in most of the countries since 2018. This dynamic of greatly increased CCP investment offering comparatively modest returns—and even triggering a more active democratic response—is one of the key findings that emerged from the study.

Journalists and civil society groups have led the way in mitigating the impact of Beijing's media influence efforts.

Nevertheless, when the full constellation of media influence tactics, response efforts, and domestic liabilities—including crackdowns on independent media and gaps in legal protections for press freedom—are taken into account, the resilience of many target countries appears more fragile. Among the 30 countries assessed using Freedom House’s new methodology, only half were found to be resilient in the face of Beijing’s media influence, and the other half were found to be vulnerable. This breakdown offers a stark warning as to the risk of complacency, even if many of the CCP’s existing campaigns have floundered.

This report offers the most comprehensive assessment to date of Beijing’s global media influence and the ways in which democracies are responding. Drawing on media investigations, interviews, scholarly publications, Chinese government sources, and on-the-ground research by local analysts, it covers developments in 30 countries during the period from January 2019 to December 2021. It updates and expands upon two previous Freedom House studies published in 2013 1 and 2020, 2 and it focuses largely on democracies to provide a more in-depth understanding of the deployment and reception of influence tactics in countries that possess relatively strong institutional protections for media freedom. Finally, the report offers recommendations to governments, the media sector, technology firms, and civil society groups on how they can bolster democratic defenses against CCP interference.

%20gettyimages-1300308201%20(1)8fe2.jpg?itok=-ZmSO2OM)

- 1 Sarah Cook, The Long Shadow of Chinese Censorship: How the Communist Party’s Media Restrictions Affect News Outlets around the World (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance at the National Endowment for Democracy, October 2013), https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CIMA-China_Sarah%20…

- 2 Sarah Cook, Beijing’s Global Megaphone: The Expansion of Chinese Communist Party Media Influence Since 2017, Freedom House, January 2020, https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/beijings-global-meg…

The goals and narratives of Beijing's influence campaign

At the beginning of this report’s coverage period in January 2019, the CCP leadership appeared to be in a strong position, both domestically and internationally. Xi Jinping had successfully rewritten the constitution to remove limits on his tenure as president, and the party was sitting atop the world’s second-largest economy, a tightly controlled information environment at home, and a growing apparatus for exerting media influence abroad. But as the next three years progressed, the regime suffered a series of unprecedented, self-inflicted blows to its legitimacy: a crackdown on large-scale prodemocracy protests in Hong Kong, the attempted cover-up of the COVID-19 outbreak by officials in Wuhan and the central government’s draconian pandemic response, related economic contraction and mismanagement, and a regular drumbeat of credible exposés regarding authorities’ brutal treatment of ethnic minority populations in Xinjiang.

China’s state media, diplomats, and other foreign-facing entities have been tasked with addressing these reputational challenges, expanding Beijing’s global influence, ensuring openness to Chinese investment, and limiting any international speech or actions that are perceived to threaten the CCP’s grip on power. Their efforts include both promotion of preferred narratives—about China, its regime, or its foreign policy priorities—and more aggressive attempts to marginalize, discredit, or entirely suppress any anti-CCP voices, incisive political commentary, or media exposés that present the Chinese government and its leaders in a negative light.

To achieve the regime’s goals, Chinese diplomats and state media outlets have invested significant resources in advancing particular narratives. The target audiences include foreign news consumers, Chinese expatriate or diaspora communities, and observers back home in China. In many countries, Chinese state propaganda includes a standard package of messages showcasing China’s economic and technological prowess, celebrating key anniversaries or the benefits of close bilateral relations, and highlighting attractive elements of Chinese culture. During the pandemic, there has been a major focus on applauding Beijing’s medical aid—such as the provision of masks, protective equipment, and Chinese-made vaccines. Many of these common themes are augmented with customized details intended to resonate with local audiences, and they are delivered in a wide range of languages. Chinese state media have leveraged numerous outlets and social media accounts that produce content in national or regional languages such as Kiswahili, Sinhala, and Romanian. In all 30 countries under study, CCP-linked actors published content in at least one major local language, and often in more than one.

But this study’s examination of state media content across the full sample of countries since 2019 also identified more problematic types of messaging. In every country, Chinese diplomats or state media outlets openly promoted falsehoods or misleading content to news consumers—on topics including the origins of COVID-19, the efficacy of certain vaccines, and prodemocracy protests in Hong Kong—in an apparent attempt to confuse foreign audiences and deflect criticism. Moreover, there was a concerted effort to whitewash and deny the human rights atrocities and violations of international law being committed against members of ethnic and religious minority groups in Xinjiang. Lastly, Chinese state-affiliated actors adopted stridently anti-American or anti-Western messaging to rebuff local concerns about Chinese state-linked activities, including those related to investment projects, opaque loans, or military expansionism, by attributing such concerns to a “Cold War mentality” or a misguided US-led attempt to “contain China.”

The full range of tactics that are now being deployed go far beyond simple propaganda messaging. They involve deliberate efforts to conceal the source of pro-Beijing content and to censor unfavorable views. In at least some countries, activities by CCP-linked actors appeared to be aimed at gaining influence over key nodes in the media infrastructure, undermining electoral integrity and social cohesion, or exporting authoritarian approaches to journalism and information control.

Expanding authoritarian media influence tactics

The CCP and its proxies engage in an array of media influence tactics, including propaganda, disinformation campaigns, censorship and intimidation, control over content-distribution infrastructure, trainings for media workers and officials, and co-optation of media serving local Chinese diaspora populations. The 30 in-depth country narratives attached to this study analyze Beijing’s activities in each of these six categories, illustrating how such avenues of influence are utilized in different combinations by varied CCP-linked actors around the world.

gettyimages-11376750151d9a.jpg?itok=KlWJ5K-5)

Although the precise mixture of tactics varies from country to country, a global perspective reveals several noteworthy trends:

- Increasing Beijing-backed content in mainstream media: Content-sharing agreements and other partnerships with mainstream media are the most significant avenue through which Chinese state media reach large local audiences. The practice allows them to inject Chinese state-produced or Beijing-friendly material into print, television, radio, and online outlets that reach more news consumers and garner greater trust than Chinese state outlets are able to achieve on their own. The labeling of the content often fails to clearly inform readers and viewers that it came from Chinese state outlets. Examples of content placements by Beijing-backed entities were found in over 130 news outlets across 30 countries, reaching massive audiences. The Chinese embassy in India, for instance, has published advertorials in the Hindu, an English-language newspaper with an estimated daily readership of six million people. 1 Besides inserted content, coproduction arrangements in 12 countries involved the Chinese side providing technical support or resources to aid reporting in or on China by their foreign counterparts in exchange for a degree of editorial control over the finished product. In nine countries—such as Romania and Kenya—monetary compensation or gifts like electronic devices were also offered for the publication of pro-Beijing articles written by local journalists or commentators. Multiple China-based entities with CCP ties—ranging from flagship state news outlets like Xinhua News Agency, whose editorial lines are tightly controlled by the party, to provincial governments and companies with close CCP ties such as Huawei—are aggressively promoting such partnerships. New agreements were signed or upgraded in 16 of the 30 countries assessed since 2019. >> Read more on this trend

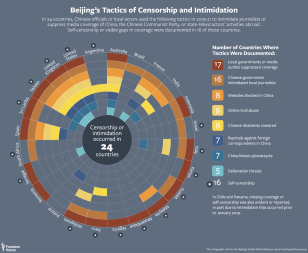

- A rise in coercive tactics: More aggressive activities such as targeted intimidation of individual reporters, cyberbullying, and cyberattacks against disfavored news outlets have expanded since 2019, reaching 24 of the 30 countries under study in some form. In half of the countries examined, Chinese diplomats and other government representatives took actions to intimidate, harass, or pressure journalists, editors, or commentators in response to their coverage, at times issuing demands to retract or delete unfavorable content. The requests are often backed up by implicit or explicit threats of harm to bilateral relations, withdrawal of advertising, defamation suits, or other legal repercussions if the media outlet, journalist, or commentator does not comply. In August 2021, the Chinese embassy in Kuwait successfully pressured the Arab Times to delete from its website an interview with Taiwan’s foreign minister after it was published in print. The online article was replaced with a statement from the embassy itself. 2 Hong Kong authorities and the Chinese telecommunications firm Huawei have joined Chinese officials and diplomats in requesting censorship or engaging in legal harassment in countries such as France and the United Kingdom. In Israel, Hong Kong authorities asked a website-hosting company to shutter a prodemocracy website and warned that refusal could result in fines or prison time for employees under the territory’s National Security Law. 3 In 17 countries, local officials, media owners, and top executives also intervened on their own initiative or at the Chinese embassy’s request to suppress news coverage that was disfavored by Beijing. >> Read more on this trend

- Covert activities and manipulation on global social media platforms: Well-known international platforms like Facebook and Twitter are an increasingly important and visible avenue for content dissemination by Chinese diplomats and state media outlets. In addition to global accounts that have gained tens of millions of followers, this study found country-specific accounts run by a diplomat or state media outlet in 28 of the 30 countries examined. Accounts affiliated with China Radio International and diplomats who genuinely engaged with local users appeared to gain authentic traction, even as others operated by Chinese officials or media entities were largely ignored or mocked by users. These mixed results may have motivated the turn to emerging tactics involving covert manipulation, such as the purchase of fake followers. Armies of fake accounts that artificially amplify posts from diplomats were found in half of the countries assessed. Related initiatives to pay or train unaffiliated social media influencers to promote pro-Beijing content to their followers, without revealing their CCP ties, occurred in Taiwan, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In nine countries, there was at least one targeted disinformation campaign that employed networks of fake accounts to spread falsehoods or sow confusion. Several such campaigns reflected not just attempts to manipulate news and information about human rights abuses in China or Beijing’s foreign policy priorities, but also a disconcerting trend of meddling in the domestic politics of the target country. >> Read more on this trend

- 1 Further citations for information in this essay that was drawn from the study's individual country reports can be found separately in those reports, which are available on the Freedom House website: www.freedomhouse.org . “Indian Media Published Special Page on Celebrating the 72nd Anniversary of Founding of the People’s Republic of China,” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of India, October 1, 2021, http://in.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/xwfw/xxfb/202110/t20211001_9571016.h… .

- 2 Lin Chia-nan, “China’s ‘Arab Times’ bullying condemned,’ Taipei Times, August 4, 2021, https://taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2021/08/04/2003761991

- 3 The company indeed removed the website, but after activists exposed the incident to international media, the firm backtracked, apologized, reinstated the site, and committed to reconsidering their screening process for future requests. “Israeli hosting firm Wix removes Hong Kong democracy website after police order,” Agence France Presse, June 5, 2021, https://www.timesofisrael.com/israeli-hosting-firm-wix-removes-hong-kon…

Beijing retains heavy influence over content consumed by Chinese speakers in much of the world, as the CCP considers potential political dissent among the global diaspora to be a key threat to regime security. In 28 of the 30 countries assessed, state-owned or pro-Beijing media played a dominant role shaping news content available to Chinese speakers, especially via the popular WeChat social media application. Chinese diaspora news outlets or politicians who wish to broadcast posts to Chinese speakers outside China via the platform’s “official account” feature are subject to the same politicized censorship that is applied to accounts inside China, forcing administrators to screen the shared content. 1

- 1 Yang, Fan, Luke Heemsbergen, and P. David Marshall. “Studying WeChat Official Accounts with Novel ‘Backend-in’ and ‘Traceback’ Methods: Walking through Platforms Back-to-Front and Past-to-Present.” Media International Australia 184, no. 1 (August 2022): 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X221088052 .

Hong Kong authorities and the Chinese telecommunications firm Huawei have joined Chinese diplomats in threatening reprisals over unfavorable content.

Several potentially important avenues of influence—such as the purchase of stakes in foreign news outlets and the export of censorship technologies for use by foreign governments—have not yet been widely exploited by Beijing. Nevertheless, both of those activities did occur in the study’s sample, and they could become more common in the future. Moreover, in many countries, China-based companies with close CCP ties have gained a foothold in key sectors associated with content distribution, including social media and news aggregation (Tencent and ByteDance), digital television (StarTimes), and mobile devices and telecommunications infrastructure (Xiaomi and Huawei). 1 Although systematic manipulation of information flows in politically and socially meaningful ways has not yet occurred, occasional incidents or evidence of latent capabilities have been documented in several countries. 2

- 1 Many China-based companies with international operations have announced the establishment of CCP committees within their headquarters in China. Four of the five companies listed (Huawei, Tencent, Xiaomi, and StarTimes) have chief executives or founders who publicly affirm their party membership, previously worked in the party’s propaganda department, or served recently as deputies to the National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp legislature. Many of them also owe their growth and sectoral dominance to support from the party, which leaves them more beholden to CCP directives. Elsa Kania, “Much ado about Huawei (part 2),” The Strategist, ASPI, March 28, 2018, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/much-ado-huawei-part-2/ . [Tencent] “[Party Building] Tencent: When the ‘Penguin’ Wears the Party Emblem,” CCP Member Online [Chinese], April 2, 2018, https://news.12371.cn/2018/04/02/ARTI1522647889151198.shtml . Kathy Gao, “China’s largest smartphone maker Xiaomi sets up Communist Party committee,” South China Morning Post, June 29, 2015, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/1828191/china… . Yaqiu Wang, “Targeting TikTok’s privacy alone misses a larger issue: Chinese state control,” Quartz, January 24, 2020, https://qz.com/1788836/targeting-tiktoks-privacy-alone-misses-a-much-la… .“Who is Ren Zhengfei?” US-China Perception Monitor, accessed August 4, 2022, https://uscnpm.org/who-is-ren-zhengfei/ . Iris Deng and Xinmei Shen, “China’s ‘two sessions’: Tencent boss Pony Ma makes his mark in key Beijing political gala with new proposals,” South China Morning Post, March 4, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/tech/big-tech/article/3124037/chinas-two-sessions-… . “Two sessions: Ideas from tech entrepreneurs,” China Daily, accessed August 4, 2022, http://ex.chinadaily.com.cn/exchange/partners/45/rss/channel/www/column… . “Chapter 3: China’s Strategic Aims in Africa,” in the US China Security and Economic Commission’s 2020 Annual Report, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Chapter_1_Section_3--C… .

- 2 In Indonesia, a media investigation revealed that a ByteDance-owned app, the news aggregator BaBe, had used moderation policies that downplayed news critical of the Chinese government from 2018-2020. The company later changed the policies to be less restrictive. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-tiktok-indonesia-exclusive/exclu… In Nigeria, the Opera News aggregator app—owned since 2016 by the PRC-based firm Beijing Kunlun—reportedly censored news stories about domestic issues, according to journalists whose posts were taken down https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/ad-aspi/2020-09/TikTok%20and%20… Samuel Okike, “Opera News Hub accused of content censorship in Nigeria,” Techpoint, January 09, 2020, https://techpoint.africa/2020/01/09/opera-news-censorship/ . A Lithuanian government cybersecurity unit in late 2021 published the findings of an investigation which found a latent list of banned terms related to China, human rights, and democracy on Xiaomi phones sold outside China that was updated in August 2021, although not activated. “Cybersecurity assessment of 5G-enabled mobile devices sold in Lithuania,” MCSC, September 27, 2021, https://www.nksc.lt/doc/en/analysis/2021-09-27_Amendment-EN-full.pdf . Multiple respondents to a Freedom House survey of Chinese diaspora journalists and commentators in the United States who worked at or published content in outlets critical of the CCP—including Voice of America, Radio Free Asia, China Digital Times, and New Tang Dynasty TV—reported experiences having posts deleted, accounts shut down, or being expelled from a group on WeChat after posting politically sensitive views or information. Separately, six plaintiffs and a Chinese prodemocracy civic group filed a lawsuit in 2021 against Tencent in California after experiencing various forms of politicized censorship on WeChat while residing in the United States. https://www.washingtonpost.com/context/citizen-power-initiatives-for-ch… https://www.dw.com/en/tiktok-censoring-lgbtq-nazi-terms-in-germany-repo…

The strengths of the democratic response

Evidence of democratic pushback against Beijing’s influence efforts proliferated during this report’s three-year coverage period. Across all of the countries under study, journalists, commentators, civic groups, regulators, technology firms, and policymakers have taken steps that reduced the impact of the CCP’s activities. In most countries, local media and civil society have been at the forefront of the response.

Many local journalists engaged in investigative reporting on China-linked projects or investments in their countries, exposing corruption, labor rights violations, environmental damage, or other harms. In 21 of the 30 countries, local outlets specifically covered CCP political and media influence. For example, a media investigation in Israel uncovered Chinese state funding for a coproduction with the Israeli public broadcaster, 1 a Malaysian news outlet mapped the introduction of false information about Hong Kong protesters into the local Chinese-language media ecosystem, 2 and an Italian outlet uncovered disproportionate coverage of Chinese COVID-19 aid on local television stations that also had content partnerships with Chinese state outlets. 3 This reporting often raised public awareness and galvanized action to counter covert or corrupt influence tactics. In at least 10 countries, news outlets discontinued their content-sharing or other partnerships with Chinese state media. In 27 countries, even outlets that continued publishing Chinese state content also published more critical or unfavorable news about the Chinese government’s policies at home or in the country in question, providing their readers with relatively balanced and diverse coverage overall. And despite the CCP’s heavy influence over Chinese diaspora media, alternative sources of information have gained ground among Chinese-language audiences in countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Brazil, Indonesia, and Malaysia, while supplying Chinese speakers around the world with online access to independent news and analysis.

One of the most common vulnerabilities identified by the analysts and interviewees consulted for this study is a low level of independent expertise on China in local media, especially regarding domestic Chinese politics and CCP foreign influence. Many outlets compensated for this gap and provided a wealth of critical reporting to news consumers by making effective and widespread use of independent international news services for their coverage of China. Meanwhile, civil society initiatives are developing a new corps of journalists and researchers to provide a local perspective on bilateral relations, monitor for problematic CCP influence efforts, and share best practices for China-related reporting. These efforts include digital news platforms dedicated to covering China’s relationship with Latin America and trainings for journalists in Nigeria, Kenya, and Tunisia on how to cover Chinese investment projects. New streams of work on CCP influence have emerged from think tanks in Indonesia, Australia, the United Kingdom, Poland, Argentina, and Romania. Joining them in many countries are local communities of Chinese dissidents, Hong Kongers, Tibetan and Uyghur exiles, and practitioners of Falun Gong who have striven to expose incidents of attempted media influence, censorship on China-based social media platforms like WeChat, and acts of transnational repression by the CCP and embassy officials.

%20gettyimages-1153801479c2a6.jpg?itok=LweeDkVZ)

- 1 Shuki Tausig, “Kan Sin” [Kan China], Seventh Eye, March 16, 2020, https://www . the7eye.org.il/365323/.

- 2 “The Hong Kong infowar in Malaysia,” Malaysiakini, August 11, 2021, https://pages.malaysiakini.com/hk-misinfo/en/ .

- 3 Gabriele Carrer, “Beijing Speaking. How the Italian Public Broadcasting TV Fell in Love with China,” Formiche, August 4, 2020, https://formiche.net/2020/04/beijing-speaking-how-italian-public-broadc… .

Countries with a strong tradition of press freedom, and with networks of organizations dedicated to upholding its principles, tend to mount a more robust response to Chinese government influence efforts. In 10 of the countries under study, local press freedom groups and the broader journalistic community mobilized in solidarity to condemn incidents in which Chinese government officials or affiliated companies engaged in intimidating or coercive behavior. In Kenya, the Media Council, a self-regulatory body for news outlets, rebuked the public broadcaster for publishing unlabeled Chinese state propaganda. 1 Taiwanese civil society has been instrumental in raising public awareness of CCP influence in local media, taking action in the form of mass demonstrations, legislative advocacy, journalist trainings, disinformation investigations, and media literacy programs.

- 1 The Media Council, “Who authored KBC’s China story?”, Media Observer Newsletter Vol. 05, Issue11, November 26, 2019. https://mediaobserver.co.ke/index.php/2019/11/25/who-authored-kbcs-chin… .

Local reporting on Chinese Communist Party political and media influence was especially effective at raising awareness and galvanizing action to counter covert and coercive tactics.

The private sector in democracies also plays an important role. Globally popular social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have improved their monitoring and response capacity over the past three years, in some cases rapidly detecting and removing fake accounts that were artificially amplifying Chinese diplomatic or state media content, spreading false information about perceived enemies of the CCP, or attempting to muddle public discourse about COVID-19, social tensions, or elections in countries such as the United States and Taiwan.

The platforms introduced labels for Chinese state-affiliated accounts and, in some cases, warnings to users about suspicious content, though there are still significant gaps in implementation. In 16 of the 30 countries, researchers found that Chinese government-affiliated accounts and news sources lacked the relevant labels on the leading social media platforms.

Legal safeguards and shortfalls in political leadership

As CCP influence efforts have received more media coverage, political elites in some countries have begun to recognize the potential threat to national interests and democratic values. However, coordinated policy responses were undertaken in only a few settings, typically those facing more aggressive influence efforts from Beijing. A more common reaction was to apply existing laws that either broadly protect press freedom or enhance scrutiny of foreign influence activities in order to support democratic resilience in China-related cases.

In some countries, particularly those where democracy was already weak or under stress, government officials responded in ways that caused harm, for instance by infringing on freedom of expression, politicizing policy debates, or encouraging discrimination against members of the Chinese diaspora. Such cases highlight the need for democracies to adopt clear and narrowly tailored rules surrounding foreign influence and investment, with independent oversight and an emphasis on transparency mechanisms rather than criminalization or censorship.

Many democracies have laws and regulations with transparency provisions that can facilitate detection of CCP influence. Journalists in several countries—including the United Kingdom, Nigeria, and Peru—made use of freedom of information laws to reveal new details about Chinese government investments, loans, or provision of Chinese-made COVID-19 vaccines to corrupt local officials. 1

In 24 of the 30 countries in this study, there were rules requiring some level of public reporting or transparency on the identity of media owners, their sources of revenue, and their other business interests. More than two-thirds of the countries under study had an investment screening and review mechanism for foreign companies’ involvement with digital information infrastructure. And in the United States, despite concerns about the vague wording and inconsistent application of the Foreign Agents Registration Act, stronger enforcement with regard to Chinese state news outlets enhanced transparency on the financing of content placements in mainstream media, within and outside of the United States. This appeared to have a beneficial deterrent effect, as media outlets sought to avoid the reputational risk of publishing CCP propaganda. 2

Rules governing foreign media ownership , especially in the broadcast sector, were present in 28 of the 30 countries, placing limitations on the size of foreign-owned stakes or requiring regulatory notification and approval before a stake is sold. Such measures help explain the paucity of examples of Chinese state entities owning stakes in foreign media outlets.

Yet these same sorts of laws and regulations can also be applied in ways that undermine free expression, particularly when they contain provisions that criminalize speech, establish politicized enforcement mechanisms, or impose sweeping, vaguely defined restrictions. In the Philippines and Mozambique, laws or proposals governing foreign ownership or content dissemination have been used by political leaders to target independent sources of news that carried criticism of the government. 3 In Poland, the government tried to justify a push to change the US ownership of a private media company by citing the need to protect Polish media from control by foreign powers like China and Russia. 4

In India, investment-screening regulations introduced in 2020 for digital media companies, including news aggregators, require any foreign personnel working in the country—either as an employee or as a consultant—to obtain a security clearance from the government that can be revoked for “any reason whatsoever.” 5 In Australia, the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme has been credited with shedding light on foreign entities’ activities in the country, but it has also been criticized for lacking reporting requirements on foreign-backed expenditures and contributing to an atmosphere of suspicion affecting Chinese Australians. 6

The existing legal frameworks in many countries lack strong safeguards for press freedom or contain other weaknesses that leave the media ecosystem more vulnerable to the influence campaigns of an economically powerful authoritarian state. Fewer than half of the 30 countries assessed had laws limiting cross-ownership that would, for instance, prevent content producers and content distributors from being controlled by a single entity. In Senegal, Australia, and the United Kingdom, meanwhile, flawed defamation laws facilitated lawsuits or legal threats against journalists, news outlets, and commentators whose work addressed Chinese investment or political influence. In 11 countries—including Brazil, Panama, Peru, Poland, and India—powerful political and economic actors have similarly used civil and criminal defamation suits in recent years to penalize and deter critical news coverage unrelated to China, indicating that journalists in those settings could also be vulnerable to the suppression of reporting related to CCP interests. Only nine of the 30 countries had anti-SLAPP (strategic lawsuits against public participation) laws or legal precedents in place to protect the work of journalists.

- 1 Rowan Philip, “Insider Access to Chinese Vaccines: A Case Study in Pandemic Corruption in Peru,” Global Investigative Journalism Network, August 4, 2021, https://gijn.org/2021/08/04/insider-access-to-chinese-vaccines-a-case-s… .

- 2 Yuichiro Kakutani, “NYT Quietly Scrubs Chinese Propaganda,” August 4, 2020, https://freebeacon.com/media/nyt-quietly-scrubs-chinese-propaganda/ . “Amendment to Registration Statement: China Daily Distribution Corporation,” US Department of Justice, June 1, 2020, https://efile.fara.gov/docs/3457-Amendment-20200601-2.pdf .

- 3 Neil Jerome Morales, Karen Lema, “Philippine regulator revokes news site’s license over ownership rules, media outraged,” Reuters, January 15, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-philippines-media/philippine-regulat… ; “Press freedom in Mozambique under pressure,” DW, March 23, 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/press-freedom-in-mozambique-under-pressure/a-5696… ; see also: “Mozambique wants to ‘control access to information’ with new media laws,” Zitamar News, April 8, 2021, https://zitamar.com/mozambique-wants-to-control-access-to-information-w… .

- 4 Maciej Witucki, “Experts React: How Far Will Poland Push Away Its friends?” New Atlanticist (blog), Atlantic Council, August 12, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/experts-react-how… . Anna Wlodarczak-semczuk and Pawel Florkiewicz, “Polish President Vetoes Media Bill, US Welcomes Move,” Reuters, December 27, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/polish-president-says-he… .

- 5 “FDI Cap on Digital Media: Security Clearance for Foreign Employees, Aggregators Also Roped In,” The Wire, October 16, 2020. https://thewire.in/business/fdi-cap-digital-media-foreign-employees-inv… .

- 6 Tarun Krishnakumar, “FITS and starts,” Lowy Institute, September 3, 2020, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/fits-and-starts . Kirsty Needham, “Australia’s foreign interference laws fueled suspicion of Chinese community—report,” November 2, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/australias-foreign-interference-laws-fuel… .

Laws and regulations with transparency provisions facilitated detection of Chinese Communist Party influence.

Rather than acting to address such vulnerabilities and fortify democratic resilience, government officials in 19 of the 30 countries have increased their own attacks on independent media, journalists, and civil society since 2019. Media outlets operating in more politically hostile or physically dangerous environments have less capacity to expose and resist the influence tactics deployed by the CCP and its proxies, especially if local political elites favor close ties with Beijing. In Ghana, Malaysia, Mozambique, Senegal, and Kuwait, local officials used their own political clout or restrictive regulations to suppress critical reporting or override independent oversight related to China.

In Malaysia and the Philippines, the same independent news outlets that have published investigative reports exposing China-linked disinformation campaigns have been at the receiving end of intense political pressure and judicial harassment because of critical coverage of their own governments.

Awareness of the threat posed by Beijing’s efforts is undoubtedly growing around the world. While some political leaders in 23 countries—including presidents, prime ministers, foreign ministers, and members of parliament—echoed CCP talking points in their own comments to local media, other elected representatives in more than half of the countries in this study publicly expressed concern over the covert, coercive, or corrupting aspects of CCP influence campaigns, including in the political, media, and information sectors. They called parliamentary hearings or addressed questions to government ministers on topics such as the impact of the Belt and Road Initiative, 1 Chinese government influence in academia, 2 foreign interference through social media, 3 and official responses to the persecution of Muslims in Xinjiang. 4 In many cases, policymakers were careful to differentiate between the CCP and ordinary Chinese people.

Nevertheless, some politicians and public figures used the pretext of CCP interference to lash out indiscriminately at China-linked targets, for instance by enacting arbitrary bans on popular mobile phone applications—as occurred in India and was attempted in the United States. In a more troubling phenomenon, local political leaders or prominent media personalities in 13 countries appeared to distort legitimate concerns about Beijing’s influence in a manner that fueled xenophobic, anti-Chinese sentiment. This seemingly contributed to hate crimes or unsubstantiated accusations of spying for members of the Chinese diaspora in eight countries.

- 1 Lok Sabha, “Parliamentary Question No. 849, One Belt One Road Initiative,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, June 26, 2019, https://mea.gov.in/lok-sabha.htm?dtl/31484/QUESTION+NO849+ONE+BELT+AND+… .

- 2 Sénat [Senate], “Influences Étatiques Extra-Européennes” [Extra-European state influence], October 19, 2021, http:// www.senat.fr/espace_presse/actualites/202109/influences_etatiques_extra… .

- 3 “Foreign interference through social media,” Parliament of Australia, December 5, 2019, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Foreign… .

- 4 Farhan Al-Shammari, "رداً على سؤال برلماني لهايف صباح الخالد: الصين تعامل مُسلمي الإيغور كبقية مواطنيها” [In response to a parliamentary question for Hayve Sabah Al-Khaled: China treats Uyghur Muslims like the rest of its citizens], Al Rai, November 7, 2019, https://www.alraimedia.com/article/867580/محليات/صباح-الخالد-الصين-تعام…

Assessing the impact of Beijing’s media influence

As the CCP devotes billions of dollars a year to its foreign propaganda and censorship efforts, it is important to ask how successful they are in different parts of the world, and what effects this could have on the health of global democracy in the future. It is significant that Chinese state narratives and content do not dominate coverage of China in most countries. Indeed, media outlets around the world continue to publish daily news that the CCP would prefer to quash and the public in many democracies is highly skeptical of obvious Chinese state propaganda.

Still, Beijing’s media influence projects have achieved results with regard to limiting critical original reporting and commentary on China in many countries, establishing dominance over Chinese-language media, and building a foundation for further manipulation. Faced with implicit or explicit threats of lost advertising, reduced access to China or Chinese diplomats, harm to relatives residing in China, or damage to bilateral relations, journalists and commentators in 18 countries in this study reportedly engaged in self-censorship or more cautious reporting on topics that are likely to anger the Chinese government.

%20gettyimages-1236885558dffa.jpg?itok=0M-BnQKQ)

Despite Beijing's efforts, Chinese state narratives and content do not dominate coverage of China in most countries.

These achievements alone grant the CCP a significant ability to reduce transparency and distort policy discussions on topics of vital importance. Many governments are making decisions about agreements with the Chinese state or China-based companies that could affect their countries for years to come in terms of national security, political autonomy, economic development, public debt, public health, and environmental degradation. Such agreements deserve scrutiny, including open debate about their advantages and disadvantages, rather than back-room negotiations and vacuous “win-win” rhetoric. In places like Nigeria, Panama, and the Philippines, public suspicion and backlash emerged after local officials’ corrupt dealings linked to China were exposed in the media. But thanks in part to Beijing’s influence efforts, many bilateral accords are signed under conditions of opacity rather than transparency.

The suppression of independent reporting about China-related topics, including through reprisals against outlets that already struggle to survive in a competitive and financially unstable industry, also has the effect of obstructing public and elite understanding of China itself, its ruling party, and its globally active corporations. News consumers and businesses are less able to make informed judgments about the political stability of a major trading partner, respond to global health and environmental challenges in which China plays a pivotal role, or take action to support freedom and justice for China’s people. Instead, aggressive behavior toward journalists globally by Chinese diplomats, companies like Huawei, and pro-Beijing internet trolls brings China’s authoritarian reality to foreign shores, complete with the associated fear of reprisals and self-censorship. This is particularly palpable in Chinese expatriate and exile communities, but it is increasingly evident among non-Chinese journalists and commentators as well.

Perhaps the most disturbing result of the CCP’s global media influence campaign is the extent to which it helps the regime avoid accountability for gross violations of international law, such as the persecution of minority populations in Xinjiang, the demolition of political rights and civil liberties in Hong Kong, and various acts of transnational repression targeting dissidents overseas. When a permanent member of the UN Security Council is able to commit atrocities and ignore international treaties with impunity, it erodes the integrity of the global human rights system as a whole, encouraging similar abuses by other regimes.

Of course, the effects of Beijing’s worldwide engagement in the media and information sector are not uniformly negative. In fact, it would not have achieved even its limited success to date if it were not addressing genuine needs. The availability of Chinese mobile technology and digital television services has expanded access to information and communication for millions of people, particularly in Africa and Southeast Asia. The provision of broadcasting equipment or uptake of a user-friendly mobile application like WeChat can empower local media and diaspora communities, even if they may also skew competition or facilitate surveillance and censorship. Any initiatives by democratic governments to counter CCP media influence efforts must take these factors into consideration.

When operating in democracies, Chinese diplomats, state media outlets, and their proxies have encountered serious obstacles.

Conclusion: Growing investment, limited returns

For at least the past three decades, the CCP has sought to extend the reach of its robust propaganda and censorship apparatus beyond China’s borders. Its first foreign influence efforts targeted Chinese-speaking communities in the aftermath of the regime’s brutal crackdown on the 1989 prodemocracy movement, whose calls for freedom were widely supported by Chinese people living overseas. But since the early 2000s, acting on instructions from top leaders, CCP officials have invested billions of dollars in a far more ambitious campaign to shape media content and narratives around the world and in multiple languages. This mission has gained urgency and significance since 2019, as global audiences have displayed sympathy toward prodemocracy protesters in Hong Kong and Uyghurs detained in Xinjiang, while blaming Chinese officials for suppressing information about the initial outbreak of COVID-19.

The past three years have been marked by an increase in CCP media influence efforts and the emergence of new tactics on the one hand, but also by an apparent decline in the global reputation of Beijing and Xi Jinping on the other, particularly among residents of democracies. Indeed, when operating in democracies, Chinese diplomats, state media outlets, and their proxies have encountered serious obstacles. In addition to the underlying resilience associated with democratic protections for media freedom, there has been a growing public awareness of Beijing’s activities and more diligent work by governments, investigative journalists, and civil society activists to detect, expose, and resist certain forms of influence.

The CCP’s own actions often undermine the narratives it seeks to promote. Its domestic human rights abuses and aggressive foreign policy stances undercut the positive story that Chinese diplomats and state media are trying to tell, of a responsible international stakeholder and a benign if authoritarian governance model. International and local media have covered these developments, and in 23 out of the 30 countries in this study, public opinion has become less favorable to China or the Chinese government.

These outcomes illustrate the importance of rights-respecting responses to authoritarian media influence efforts and of enhancements to underlying democratic resilience. In confronting the challenge of global authoritarianism, democracies are most effective when they uphold the very values and institutions that distinguish them from authoritarian regimes, including protections and support for independent media and civil society. Long-term success will require further action—including investments of financial and human capital, creativity, and innovation—to defend media independence against both foreign and domestic pressures. But despite fears about the supposed efficiency of autocratic models, the findings of this study offer substantial evidence that the core components of democracy are capable of insulating free societies against Beijing’s authoritarian influence.

Intimidation and Censorship

The Sharper Edge of Beijing’s Influence

Within its own borders, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) presides over the world’s most sophisticated and multifaceted apparatus for information control. The regime uses direct censorship of traditional media, legal and technical controls over social media, and politicized prosecutions to stifle independent reporting and commentary. In trying to influence foreign media, Beijing must work with a much more limited set of tools.

Nevertheless, China’s leaders have cast a shadow over news coverage abroad through a combination of actions taken at home, pressures applied against foreign journalists and editors in targeted countries, and incentives that encourage foreign media owners and governments to preemptively obstruct reporting on China-related topics. Even as many journalists and outlets push back, the intimidation, threats, and economic leverage emanating from Beijing have taken a toll.

Ten years ago, the CCP’s censorship of foreign media appeared to focus on international outlets operating within China and Chinese-language outlets based abroad, including those in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Today, some of the same tactics are being applied to mainstream media in a growing number of countries. The restrictive, censorial side of Beijing’s influence efforts remains much less visible than the daily barrage of Chinese state propaganda being disseminated globally. Yet it has affected not only what news is reported in many countries, but also how and by whom.

Constraining foreign correspondents and journalists in exile

At the center of the Chinese government’s strategy for controlling international news coverage about the country and its rulers are the tight restrictions—and increasing intimidation—applied to China-based correspondents for foreign outlets. Conditions for these journalists have deteriorated considerably since 2019, exacerbating an already difficult situation.

New and more sinister tactics have been added to the long-standing practices of heavy surveillance and restricted travel to sensitive locations like Xinjiang, Tibet, and protest sites—all of which have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Foreign correspondents have been subjected to mass expulsions or visa rejections based on nationality, attempted interrogations in connection with national security charges, and questionable lawsuits by sources who had explicitly agreed to be interviewed. 1 The spouses and children of foreign correspondents have also been harassed, prompting some to leave the country. In addition to correspondents from countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Taiwan—whose relations with China have become more adversarial in recent years—reporters from Poland, Spain, and France have experienced expulsions or restrictions on reporting within China since 2019.

Restrictions on Chinese nationals who work as research assistants for foreign journalists—subject to strict oversight by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs—have also tightened. The December 2020 detention of Chinese national Haze Fan, who at the time was working for Bloomberg News, on opaque state security charges was especially chilling for her colleagues and others in the industry. Fan was released on bail in June 2022 after more than a year in custody, but her case was still pending at the time of writing. 2

- 1 Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China (FCCC), 2021: Locked Down or Kicked Out Covering China (Beijing: FCCC, February 2022), https://opcofamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2021-FCCC-Report-FI… .

- 2 Madeleine Lim, “China Has Released Bloomberg News Staffer Haze Fan on Bail,” Bloomberg, June 14, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-14/china-has-released-b… .

Even as many journalists and outlets push back, the intimidation, threats, and economic leverage emanating from Beijing have taken a toll.

Severe limitations on the work of foreign correspondents from a handful of key countries have a multiplier effect on international coverage of China, given how widely their reporting is used by outlets in other countries that cannot afford their own overseas bureaus; many Chinese nationals, whether at home or abroad, also rely on such news organizations for unbiased information about their own country.

Uncertainty surrounding journalist visas and local hiring adds expenses, raising the cost of entry and limiting the number of outlets that can maintain reporters in China or dispatch them beyond major cities like Beijing and Shanghai. The content vacuum created by the regime’s restrictions then provides an opening for material from official Chinese news services like Xinhua and China Central Television (CCTV), which Beijing has aggressively promoted in foreign media markets.

Severe restrictions on foreign correspondents have a multiplier effect on international coverage of China.

In addition to increasing pressure on foreign correspondents in China, Chinese internal security forces have gone so far as to threaten, harass, or imprison the family members of journalists based outside the country who expose rights violations or otherwise report news that is disfavored by Beijing. Such incidents occurred in five countries under study—Australia, India, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States—with the relatives of US-based Uyghur reporters for Radio Free Asia serving long prison sentences. 1 Intimidation of this sort has likely occurred elsewhere among members of the Chinese, Tibetan, and Uyghur diasporas, but it is difficult to document. The threats create a strong incentive for self-censorship, depriving international audiences of access to information from journalists with intimate knowledge of China and its ethnic and religious minority populations.

- 1 “The Families Left Behind: RFA’s Uyghur Reporters Tell the Stories of Their Family Members’ Detentions,” Radio Free Asia, accessed August 19, 2022, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/special/uyghurfamilies/ .

Censorship beyond China

The CCP regime’s efforts to use threats, bullying, and economic leverage to suppress disfavored reporting extend far beyond China’s borders. In 16 of the 30 countries examined in this study, Chinese diplomats or other government representatives took steps to intimidate, harass, or pressure journalists, editors, or commentators in response to their coverage. The tone of the interventions was not that of polite disagreement. Public castigation of a journalist or commentator by the sitting ambassador of the world’s most powerful authoritarian regime—as occurred in France and Peru—will inevitably intimidate. In Italy, similar behavior by an embassy spokesperson caused a local reporter to reconsider attending a newsworthy event surrounding the signing of a bilateral agreement.

Private forms of pressure appear to be more common, with Chinese representatives reaching out directly to reporters, commentators, or editors and urging them to issue a retraction or apology. Journalists in the United Kingdom reported that their editors received long, angry “screaming down the line” phone calls from the Chinese embassy following stories that were unfavorable to the CCP. 1 The calls, emails, and letters from the embassy often contain veiled threats—or in incidents in Israel, Australia, and Ghana, explicit threats—of damage to bilateral relations.

Threats of legal or economic reprisals against a news outlet, such as defamation suits or withdrawal of advertising, were also reported in some cases. In 2018, a Chinese state-owned company threatened to sue a leading Kenyan newspaper, the Standard, for its investigative reporting on abuses at the railway operated by the firm. The paper declined to retract the story or apologize. According to its editor, “the Chinese embassy and their communications manager canceled all their advertisements with the Standard and withdrew the [paid advertorial] supplement.” He added, “They demanded that we had to stop negative coverage.” 2

Although sometimes rebuffed, embassies’ efforts have yielded results, especially when they apply pressure to the upper management of media outlets in less democratic or more economically challenging environments. In Nigeria, the Chinese embassy has reportedly reached out to editors at major news outlets and paid journalists not to cover negative stories about China. The commissions editor at a major online publication reported in an interview: “I know they give money to journalists so that they will not do critical stories and then they do breakfast meetings with editors early in the morning. They build relationships with editors across media organizations.” 3

- 1 See this report’s country study on the United Kingdom by Angeli Datt and Sam Dunning: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/uni… .

- 2 Chrispin Mwakideu, “Experts Warn of China’s Growing Media Influence in Africa,” Deutsche Welle, January 29, 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/experts-warn-of-chinas-growing-media-influence-in… .

- 3 Interview with former editor at a Nigerian media outlet who requested anonymity, Nigeria, January 2022. See this report's country study on Nigeria by Angeli Datt and Emeka Umejei: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/nig… .

In 12 countries, local officials took measures to suppress coverage that might be disfavored by the Chinese government.

Implicit threats to journalists’ work, such as loss of access to embassy personnel for future interviews or exclusion from subsidized press trips to China, are also used to discourage disfavored reporting. In October 2020, when the Chinese embassy sent a letter to Indian media asking them to respect the “One China” principle and not report on Taiwan’s national day, it contained veiled threats of restricted access to the embassy for those who did not comply. 1 In Italy, journalists who had published critical coverage about the Chinese regime or embassy were reportedly excluded from groups on the WhatsApp messaging platform that facilitated access to Chinese diplomats for comment. 2

Chinese state representatives have sometimes taken an indirect approach, pressuring local governments to intervene and either “guide” the media or shun outlets that persist in their criticism. A municipal council in Sydney, Australia, barred the Vision China Times, a local Chinese-language paper that was critical of the CCP, from sponsoring a Chinese New Year event after sustained pressure from the Chinese consulate, according to emails revealed through a 2019 freedom of information request. 3

A country’s authorities may also interfere with the media’s coverage of China and local Chinese activities on their own initiative, whether to curry favor with Beijing, to defend shared interests, or for other reasons. In 12 countries, local officials took measures, through control of publicly funded media or regulatory enforcement, to suppress coverage that might be disfavored by the Chinese government, often without direct intervention by the embassy. In Mozambique, a provincial government blocked a private television channel from airing an evening rebroadcast of critical reporting about a Chinese company’s involvement in environmental degradation. 4 In Malaysia, the Home Ministry in late 2019 denied a publishing permit to a Chinese-language newspaper that was critical of the CCP, citing the need to protect bilateral ties. 5

- 1 Aditya Raj Kaul (@AdityaRajKaul), “#BREAKING: Chinese Embassy, New Delhi issues diktat letter to Indian media about reporting the National Day of Taiwan on Oct 10th. Says, ‘Taiwan is inalienable part of China’s territory.’ Is this an indirect threat to Indian media who cover Taiwan? @MOFA_Taiwan @digidiploTaiwan,” Twitter, October 7, 2020, https://twitter.com/AdityaRajKaul/status/1313814773830578176 . See this report’s country study on Taiwan by Angeli Datt and Jaw-Nian Huang: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/tai… .

- 2 Notes from closed-door roundtable with Italian journalists conducted by the International Federation of Journalists, February 11, 2021, on file with Freedom House. See this report’s country study on Italy by BC Han and Laura Harth: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/ita… .

- 3 Nick McKenzie, Sashka Koloff, and Mary Fallon, “China Pressured Sydney Council into Banning Media Company Critical of Communist Party,” Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), April 6, 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-04-07/china-pressured-sydney-council-o… . See this report’s country study on Australia by Angeli Datt and an anonymous local analyst: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/aus… .

- 4 Interview with a Mozambican journalist who wished to remain anonymous, January 10, 2022. A version of the broadcast remained accessible online: “Empresa chinesa invade e destrói dunas da Praia de Chongoene’’ [Chinese company invades and destroys dunes on Chongoene Beach], Centro Terra Viva, April 16, 2021, http://ctv.org.mz/empresa-chinesa-invade-e-destroi-dunas-da-praia-de-ch… , accessed May 11, 2022. See this report’s country study on Mozambique by Ellie Young and Dércio Tsandzana: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/moz… .

- 5 Communication with Falun Gong practitioner in Malaysia who wished to remain anonymous, June 2022. A copy of the message from the ministry is on file with Freedom House. See this report’s country study on Malaysia by BC Han and Benjamin Loh: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/mal… .

Huawei, Hong Kong, and hackers pile on

Chinese embassies are not the only Beijing-linked actors engaged in intimidation and censorship efforts. In a relatively new phenomenon, Hong Kong authorities and major Chinese companies with close CCP ties, like Huawei, have engaged in similar behavior. After a French researcher referred on television to Huawei being under the control of the Chinese state and the CCP in March 2019, the telecommunications firm filed a defamation suit against her, the program’s presenter, and the production company; the case was still ongoing three years later. 1

As political repression has intensified in Hong Kong since 2019, the authorities there have joined their mainland counterparts in trying to control news and information about the territory globally, using local laws that assert extraterritorial jurisdiction to restrict speech by individuals and entities based abroad. In December 2021, the Hong Kong government sent a letter to London’s Sunday Times that threatened prosecution over an editorial which had urged voters to boycott that month’s legislative elections in the territory. The letter cited a provision of the Elections Ordinance that it said applied “irrespective” of whether the offending comments were made in Hong Kong or abroad. 2

Foreign journalists and media outlets have also faced forms of online intimidation that are more difficult to trace back to the Chinese government, but the circumstantial ties are clear, and these abuses are no less problematic in terms of the psychological and financial pressures they entail.

One tactic that increased in frequency and aggressiveness during the coverage period was the use of coordinated online harassment campaigns on global social media platforms to attack journalists working for news outlets based in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom. The campaigns tended to target women of East Asian, including ethnic Chinese, descent, and they were often catalyzed by Chinese state media reports or other official comments that called out the affected individuals by name. Pro-Beijing trolls not only disparage the journalists’ coverage but, according to the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China, also “make crude sexual innuendos, including alarming threats of physical violence.” 3 One Chinese American journalist who writes for the New Yorker published an account of her experience with such cyberbullying during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City; the online trolls mocked her for being separated from her elderly mother, who was housed at a nursing facility where death rates were high. 4 Chinese-Australian researcher Vicky Xu of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute became the target of a similar campaign after coauthoring a report that documented the use of forced labor by Uyghurs in China to produce goods for export. 5 In addition to these examples from countries where tensions with China have intensified since 2019, journalists or commentators in France, Italy, Spain, and the Philippines also encountered online verbal abuse from pro-CCP trolls.

- 1 Huawei has publicly acknowledged close ties to the CCP that place the party in a strong position to influence the company, including the founder’s own party membership, an internal party committee at the firm, and the head of that committee sitting on the company’s executive board. Brice Pedroletti, “Une Chercheuse Française Poursuivie par Huawei France” [A French researcher sued by Huawei France],” Le Monde, November 26, 2019, https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2019/11/26/une-chercheuse-… ; Helene Fouquet, “Huawei Sues Critics in France over Remarks on China State Ties,” Bloomberg, November 22, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-11-22/huawei-sues-critics-… ; Elsa Kania, “Much Ado about Huawei (Part 2),” The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, March 28, 2018, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/much-ado-huawei-part-2/ ; “Who Is Ren Zhengfei?,” US-China Perception Monitor, accessed August 4, 2022, https://uscnpm.org/who-is-ren-zhengfei/ .

- 2 Gilford Law, “Letter to the Sunday Times,” December 8, 2021, https://www.brandhk.gov.hk/docs/default-source/clarifications/2021/2021… . See this report’s country study on the United Kingdom by Angeli Datt and Sam Dunning: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/uni… .

- 3 FCCC, 2021: Locked Down or Kicked Out Covering China (Beijing: FCCC, February 2022), 8, https://opcofamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2021-FCCC-Report-FI… .

- 4 Jiayang Fan, “How My Mother and I Became Chinese Propaganda,” New Yorker, September 7, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/09/14/how-my-mother-and-i-becam… . See this report’s country study on the United States by Sarah Cook and Yuichiro Kakutani: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/uni… .

- 5 Zeyi Yang, “The Anatomy of a Chinese Online Hate Campaign,” Protocol, April 9, 2021, https://www.protocol.com/china/chinese-online-hate-campaigns .

Coordinated online harassment campaigns from pro-Beijing trolls, especially against female journalists of East Asian descent, have increased since 2019.

In seven countries, meanwhile, news outlets or journalists suffered from cyberattacks that could be reasonably linked to China. 1 In March 2021, a well-known China-based hacking group gained entry to the servers of the Times of India, one of the most widely read English-language newspapers in the world, and transferred data to an off-site server. Cybersecurity researchers who investigated the breach suggested that the attackers’ motivation was “some combination of wanting to know who is talking to the media and wanting to know ahead of time what people are reporting on.” 2 In a similar attack discovered in January 2022 but believed to have been ongoing since 2020, hackers broke into the networks of the News Corporation media group, targeting the Wall Street Journal and New York Post in the United States and the Times and Sunday Times in the United Kingdom. The intruders, who were believed to be tied to Chinese intelligence services, sought to “access reporters’ emails and Google Docs, including drafts of articles.” 3 More openly disruptive forms of cyberattack, such as distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, have targeted overseas Tibetan and Chinese-language websites that are critical of the CCP, especially during politically sensitive periods, temporarily disabling their websites and increasing costs for what are already cash-strapped outlets. 4

The frequency and caliber of these cyberattacks increase the financial burden on outlets to improve their defenses, and hacking that involves data theft could put journalists and their sources at risk. If no back-up exists for a breached server or website, which is more likely at smaller, Chinese-language diaspora outlets, the most destructive digital attacks could permanently erase content that was critical of the Chinese government.

- 1 In a survey of Taiwanese journalists who report on China that was conducted for this report, two out of 13 respondents said they believed they had been the target of a hacking attempt after receiving warnings about unusual log-ins on their phones. See this report’s country study on Taiwan by Angeli Datt and Jaw-Nian Huang: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/tai… .

- 2 Dina Temple-Raston, “Report: China-Linked Hackers Take Aim at Times of India and a Biometric Bonanza,” Recorded Future, September 21, 2021, https://therecord.media/report-china-linked-hackers-take-aim-at-times-o… . See this report’s country study on India by Angeli Datt and an anonymous local analyst: https://freedomhouse.org/report/beijing-global-media-influence/2022/ind… .

- 3 Eric Tucker, “News Corp Says It Was Hacked; Believed to Be Linked to China,” WMBF News, February 4, 2022, https://www.wmbfnews.com/2022/02/04/news-corp-says-it-was-hacked-believ… ; Alexandra Bruell, Sadie Gurman, and Dustin Volz, “Cyberattack on News Corp, Believed Linked to China, Targeted Emails of Journalists, Others,” Wall Street Journal, February 4, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/cyberattack-on-news-corp-believed-linked-t… .

- 4 N. Coca, “The High-Tech War on Tibetan Communication,” Engadget, June 27, 2017, https://www.engadget.com/2017-06-27-the-high-tech-war-on-tibetan-commun… .

Preemptive self-censorship by media and businesses

The CCP has become sufficiently adept and prolific with its pressure tactics and reprisals over even minor slights that media owners, editors, and local officials will in many cases act preemptively to suppress coverage or silence critical speech, without the need for the Chinese embassy or state-linked hackers to intervene.

In 17 of the 30 countries in this study, there was evidence—uncovered through content analysis or interviews with current and former journalists—that media outlets suppressed, avoided, or reframed coverage of news events in China, such as human rights violations, or of Chinese investment projects and related political scandals in their home countries. Most outlets that engaged in such self-censorship had owners with financial interests in China or other ties to Chinese entities. The incidents occurred in countries as varied as Argentina, Brazil, Peru, South Africa, Malaysia, and Taiwan.

According to interviewees in Nigeria, outlets whose editors or publishers had a relationship with the Chinese embassy tended to “soften” reporters’ writing when they produced unfavorable articles. In Taiwan, editors and executives at outlets owned by businessmen with investments in China suppressed stories about human rights or other issues that disfavor the Chinese government. 1 A 2019 survey of 149 Taiwanese journalists found that nearly 50 percent of the respondents had been ordered by their company or supervisor to reduce reports on sensitive issues related to China. 2 Following Panama’s 2017 transfer of diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China and ahead of Chinese president Xi Jinping’s 2018 visit to the country, journalists at some Panamanian outlets were encouraged by their editors to avoid covering topics that might upset advertisers like Huawei or local businesses that appeared likely to benefit from Chinese investment. One journalist said, “I was told at the time to be less harsh on reporting [about China] because there is a danger they will pull advertising. This came from upper management.” 3