It is governments reaching across borders to silence dissent among diasporas and exiles, including through assassinations, illegal deportations, abductions, digital threats, Interpol abuse, and family intimidation .

It is a daily assault on civilians everywhere — including in democracies like the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, Australia, and South Africa.

Critical voices that challenge authoritarian rule become voices to silence. Journalists and human rights defenders . Diaspora groups and family members of exiles. Political activists, dissidents and civil society leaders .

What appear to be isolated incidents when viewed separately—an assassination here, a kidnapping there—in fact form a constant threat across the world that is affecting the lives of millions of people and changing how activists, journalists, and regular individuals go about their lives. Transnational repression is no longer an exceptional tool, but a normal and institutionalized practice for dozens of countries that seek to control their citizens abroad.

Its impact on the rights of victims is severe. Even those who are not directly targeted may decide based on the threat against their community to remain silent. This is true of the most extreme violence: a single killing or rendition sends ripples throughout a huge circle of people. But even digital threats or family intimidation—the easiest and most common forms of transnational repression—create an atmosphere of fear among exiles that pervades everyday activities.

Jamal Khashoggi was a prominent Saudi journalist who had formerly been close to the monarchy, but grew disillusioned with its repressive nature. He moved abroad in 2017 and began writing about democracy, including as a columnist for The Washington Post . In October 2018, he entered the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul to obtain documents necessary for his upcoming marriage. Saudi agents murdered him in the consulate and dismembered his body while his fiancée waited outside for him to emerge.

Masih Alinejad is an Iranian journalist, author, and women’s rights and political activist who left Iran in 2009 and lives in the United States. In July 2021, the US Department of Justice revealed a plot to kidnap Alinejad from her home in Brooklyn and return her to Iran, possibly via Venezuela. Alinejad has previously faced other tactics of transnational repression. In 2018, her sister in Iran was forced to go on state TV to denounce her. In September 2019, her brother Alireza was arrested in Iran, and sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment. In April 2020, her mother was also detained and questioned. Like many other Iranian journalists abroad, Alinejad says she receives constant digital and physical threats against her life.

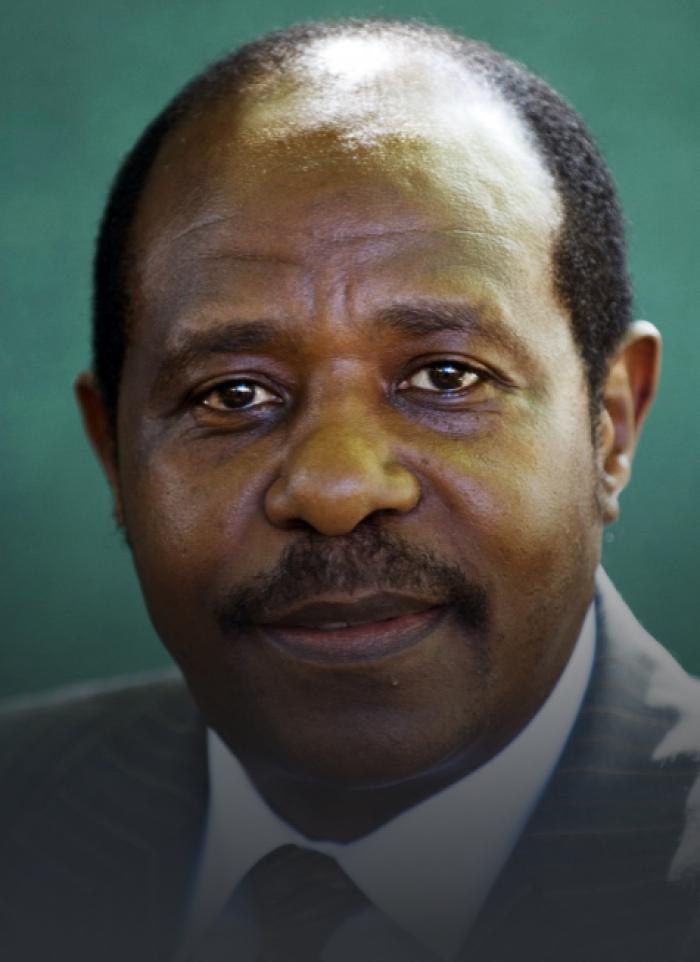

Paul Rusesabagina is a political activist best known as the real-life hero of the movie Hotel Rwanda . He fled Rwanda in the 1990s after being warned of an assassination plot against him. He became a vocal critic of the government, first living in Belgium and then relocating again to the United States to avoid persecution from the Rwandan government. In August 2020 the Rwandan government kidnapped him while he was transiting through Dubai. After being held for at least three days incommunicado, he reappeared in custody in Rwanda, where he was sentenced to 25 years in prison on charges related to terrorism.

Praphan Pipithnamporn is a Malaysian Thai anti-monarchy campaigner. She had been arrested multiple times in Thailand for her political activities and held in military detention. Fearing further persecution, she fled Thailand in January 2019 to Malaysia and registered as an asylum-seeker. Despite her protected status, however, Malaysian authorities arrested her in April 2019, and illegally returned her to Thailand in May that year.

Loujain al-Hathloul is a Saudi human rights activist known in particular for her campaigning for women’s rights in a strictly patriarchal society. In March 2018, she was detained in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, and rendered on a private plane to Saudi Arabia. She was initially released, but two months later Saudi authorities arrested her again. She was held incommunicado for 10 months, during which time she was tortured. In December 2020 she was sentenced to five years and eight months in prison. Her sentence was later suspended and she was released in February 2021, but she is banned from leaving Saudi Arabia.

Raman Pratasevich is a Belarusian political activist and journalist who sought asylum in Europe in 2019. He ran a popular Telegram channel that documented pro-democracy protests. In May 2021, Belarusian authorities faked a bomb threat to force a plane travelling from Athens to Vilnius to land in Minsk in order to arrest Pratasevich and his companion, Sofia Sapega. Shortly afterward, authorities released videos of Pratasevich that suggested he had experienced torture. Pratasevich was released from house arrest in January 2022 but still faces up to 15 years in prison in connection to his journalism.

Idris Hasan is a Uyghur human rights defender who has lived in Turkey since 2012. In July 2021, Moroccan officials, acting on an Interpol notice, arrested him upon arrival at the airport in Casablanca. The Chinese government alleges Hasan is involved with a terrorist organization, an accusation frequently levied against Uyghurs. Despite the fact that Interpol cancelled the notice shortly after his arrest, Hasan remains in detention awaiting deportation to China, where he is at risk of torture.

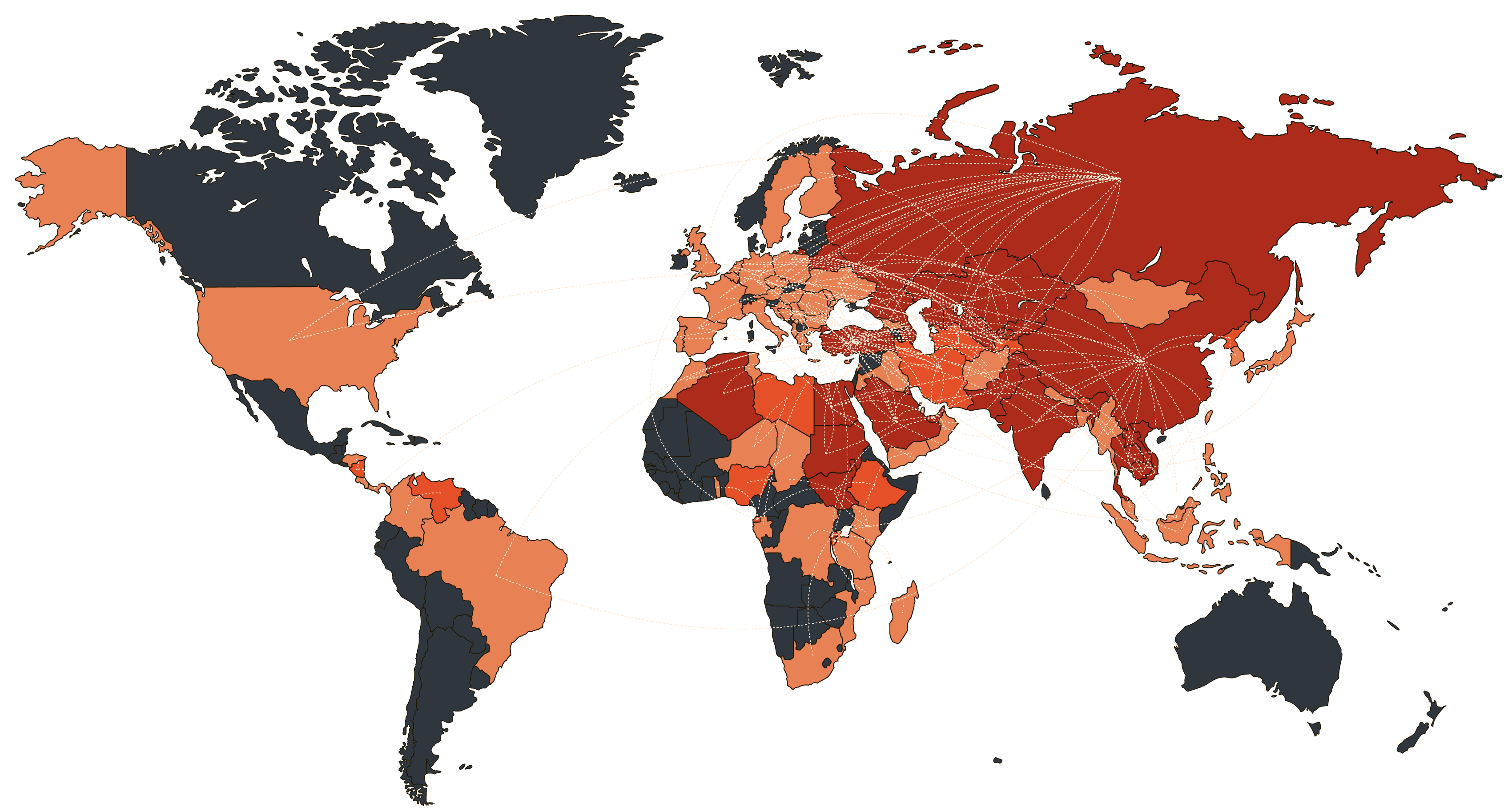

Transnational Repression takes place all over the world. We found 36 origin states using physical transnational repression in 84 host countries since 2014.

Around the globe, states are employing a toolbox of diverse and aggressive tactics to control their citizens, or sometimes even non-citizens, abroad.

Each line represents a unique origin country-host country relationship through at least one incident of physical transnational repression. Every incident catalogued in the project is not mapped.

Exiles and diasporas living in these nine countries face serious threats from abroad. The countries offer illustrative examples of policies and practices that can facilitate or prevent acts of transnational repression.

United States

United States

Germany

Germany

South Africa

South Africa

Sweden

Sweden

Turkey

Turkey

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Thailand

Thailand

Canada

Canada

Ukraine

Ukraine

Host country policies can help protect individuals from transnational repression — or make them more vulnerable to attack.

These are six countries that currently operate aggressive campaigns of transnational repression.

China

China

Turkey

Turkey

Rwanda

Rwanda

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

Russia

Russia

Iran

Iran

Authoritarian countries are silencing exiles and diasporas with tactics of fear and repression.

These tactics violate exiles’ fundamental rights and undermine the rule of law in host countries.

Origin country tactics that physically reach the individual targeted.

Origin country tactics that do not require physically reaching the individual targeted.

When origin countries restrict individuals’ ability to travel.

When origin countries manipulate host country institutions like police or immigration authorities to harass, detain, or transfer individuals.

View the full set of global and country-specific policy recommendations.

Spread the word

Two Belarusian activists are abducted from a Moscow hotel and driven over 400 miles to Minsk, where they are charged with planning a coup.

A Uyghur woman in Canada receives yet another phone call from Chinese police urging her to cooperate and threatening to detain her family members should she refuse.

A Russian man who fled to the United States after security services stole his business is held on a frivolous Interpol notice and kept in US immigration detention for a year and a half.

A Rwandan journalist applies for asylum in Mozambique and then disappears—possibly into the custody of Rwandan authorities.

Saudi officials asphyxiate and dismember an exiled Saudi journalist inside the country’s consulate in Istanbul.

All of these are examples of transnational repression, in which governments reach across national borders to silence dissent among diaspora and exile communities. They are real events that have occurred since 2014, illustrating an enormous and growing threat to activists, journalists, and migrants around the globe. Nondemocratic states are employing diverse and aggressive tactics to control their citizens, or sometimes even noncitizens, in every region of the world.

Freedom House is engaged in a multiyear study of transnational repression. Its latest report, Defending Democracy in Exile: Policy Responses to Transnational Repression , published in June 2022, examines what is being done to protect exiles and diaspora members who are being intimidated and attacked by the governments from which they fled. The report assesses the responses mounted by host governments, international organizations, and technology companies. It builds on the findings of Out of Sight, Not Out of Reach: The Global Scale and Scope of Transnational Repression —the first global study of this dangerous practice, which Freedom House released in February 2021.

The project draws on an original database of 735 direct, physical cases of transnational repression that took place between 2014 and 2021. In each incident, the origin country’s authorities physically reached an individual living abroad, whether through detention, assault, physical intimidation, unlawful deportation, rendition, or suspected assassination. Freedom House assembled cases of transnational repression from public sources, including UN and government documents, human rights reports, and credible news outlets, in order to generate a detailed picture of this global phenomenon. The database captures 36 origin states conducting physical transnational repression in 84 host countries. This total is certainly incomplete; hundreds of other physical cases that lacked sufficient documentation, especially detentions and unlawful deportations, are not included in Freedom House’s count. Nevertheless, even such a conservative tally shows that what often appear to be isolated incidents—an assassination here, a kidnapping there—actually represent a pernicious and pervasive threat to human freedom, democracy, sovereignty, and security.

Moreover, each case of physical transnational repression is only the tip of an iceberg. The chilling effect of every attack ripples out into the larger community. And beyond the physical cases compiled as part of this research are the much more widespread tactics of “everyday” transnational repression: digital threats, spyware, and coercion by proxy, such as the imprisonment of exiles’ families in the origin country. For millions of people around the world, transnational repression has become not an exceptional tool, but a common and institutionalized practice used by dozens of regimes to control people outside their borders.

Freedom House’s research shows that:

Freedom House’s first report on transnational repression, Out of Sight, Not Out of Reach , consisted of an introduction, a description of the methods of transnational repression, case studies on six states—China, Rwanda, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey—that have conducted significant transnational repression campaigns, and regional summaries covering countries not in the case studies.

The latest report, Defending Democracy in Exile , includes four essays that investigate new trends, describe best and worst practices among host country governments, explain the role of international organizations in confronting transnational repression, and demonstrate the importance of countering digital tactics. The report also features case studies on policy responses to transnational repression in nine important host countries: Canada, Germany, South Africa, Sweden, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Freedom House’s recommendations focus on what governments, technology companies, and civil society organizations can do to hold perpetrators accountable for transnational repression, increase resilience within democracies, and better protect vulnerable individuals and groups. In addition to general recommendations for policymakers, there are specific recommendations for each of the nine host countries studied.

Governments can use security, migration, and foreign policy improvements to combat transnational repression. Consistent accountability , especially in the form of targeted sanctions, will raise the cost of transnational repression for the regimes in question. Resilience efforts, particularly measures that reduce opportunities for authoritarian states to manipulate institutions within democracies, will make it harder to attack exiles and diaspora communities in practice. Protection for vulnerable people, both when they face credible threats and more broadly by respecting the right to seek asylum, will prevent harm and enable them to exercise their fundamental rights, ultimately strengthening the foundations of democracy in both host and origin countries.

Transnational repression is a serious threat to human rights, democratic governance, and state sovereignty, as well as a disturbing manifestation of global authoritarianism. But with accountability for perpetrators and compassion for their targets, it can be stopped.

The project was made possible through the generous support of the Achelis and Bodman Foundation and the National Endowment for Democracy.

To read more about the project, click here . Data is available on request from Freedom House through [email protected] . Please use the subject line “Transnational Repression Data Request.”

Potential targets of transnational repression in the United States include people who support human rights and democracy in their former homelands, and those who advocate for the well-being of friends and family they left behind.

By studying transnational repression at a global scale, Freedom House aims to explain the repercussions of these campaigns, and to help policymakers and civil society think about how they can respond to protect exiles and diasporas.

The recommendations listed below are intended to constrain the ability of states to commit acts of transnational repression and to increase accountability for perpetrators of transnational repression.

Join the Freedom House weekly newsletter