Marking 50 Years in the Struggle for Democracy

Iranian people in Izmir protest the death of Jina Mahsa Amini while in custody of the morality police in Iran. (İdil Toffolo/Alamy)

The 2023 edition of Freedom in the World is the 50th in this series of annual comparative reports. More than anything else, five decades of Freedom in the World reports demonstrate that the demand for freedom is universal.

Key Findings

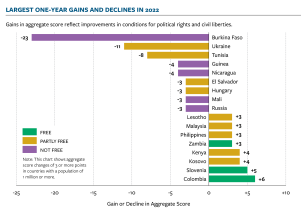

Global freedom declined for the 17th consecutive year. Moscow’s war of aggression led to devastating human rights atrocities in Ukraine. New coups and other attempts to undermine representative government destabilized Burkina Faso, Tunisia, Peru, and Brazil. Previous years’ coups and ongoing repression continued to diminish basic liberties in Guinea and constrain those in Turkey, Myanmar, and Thailand, among others. Two countries suffered downgrades in their overall freedom status: Peru moved from Free to Partly Free, and Burkina Faso moved from Partly Free to Not Free.

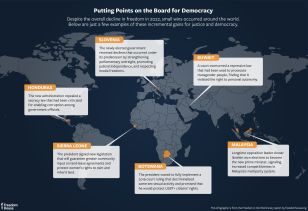

The struggle for democracy may be approaching a turning point. The gap between the number of countries that registered overall improvements in political rights and civil liberties and those that registered overall declines for 2022 was the narrowest it has ever been through 17 years of global deterioration. Thirty-four countries made improvements, and the tally of countries with declines, at 35, was the smallest recorded since the negative pattern began. The gains were driven by more competitive elections as well as a rollback of pandemic-related restrictions that had disproportionately affected freedom of assembly and freedom of movement. Two countries, Colombia and Lesotho, earned upgrades in their overall freedom status, moving from Partly Free to Free.

While authoritarians remain extremely dangerous, they are not unbeatable. The year’s events showed that autocrats are far from infallible, and their errors provide openings for democratic forces. The effects of corruption and a focus on political control at the expense of competence exposed the limits of the authoritarian models offered by Beijing, Moscow, Caracas, or Tehran. Meanwhile, democratic alliances demonstrated solidarity and vigor.

Infringement on freedom of expression has long been a key driver of global democratic decline. Over the last 17 years, the number of countries and territories that receive a score of 0 out of 4 on the report’s media freedom indicator has ballooned from 14 to 33, as journalists face persistent attacks from autocrats and their supporters while receiving inadequate protection from intimidation and violence even in some democracies. The past year brought more of the same, with media freedom coming under pressure in at least 157 countries and territories during 2022. Scores for a related indicator pertaining to freedom of personal expression have also declined over the years amid greater invasions of privacy, harassment and intimidation, and incentives to self-censor both online and offline.

The fight for freedom persists across decades. When Freedom House issued the first edition of its global survey in 1973, 44 of 148 countries were rated Free. Today, 84 of 195 countries are Free. Over the past 50 years, consolidated democracies have not only emerged from deeply repressive environments but also proven to be remarkably resilient in the face of new challenges. Although democratization has slowed and encountered setbacks, ordinary people around the world, including in Iran, China, and Cuba, continue to defend their rights against authoritarian encroachment.

Executive Summary

T he global struggle for democracy approached a possible turning point in 2022. The gap between the number of countries that registered overall improvements in political rights and civil liberties and those that registered overall declines was the narrowest it has ever been through 17 consecutive years of deterioration.

The most serious setbacks for freedom and democracy were the result of war, coups, and attacks on democratic institutions by illiberal incumbents. The authoritarian regime in Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in a bid to scuttle that country’s hard-won democratic progress. New coups and other attempts to undermine representative government destabilized Burkina Faso, Tunisia, Peru, and Brazil. Previous years’ coups and ongoing repression continued to diminish basic liberties in Guinea and constrain those in settings such as Turkey, Myanmar, and Thailand. Afghanistan’s Taliban regime barred girls from receiving an education in the midst of an ongoing economic and humanitarian crisis. Governments and occupying powers used violence and other means to destroy cultures and change the ethnic composition of populations in 21 countries and territories, including Ukraine, Ethiopia, and Myanmar.

A total of 34 countries showed improvements in political rights and civil liberties, compared with 35 that lost ground, signaling a possible slowdown in the global decline. Democratic gains were achieved through more transparent and competitive elections in Lesotho, Colombia, and Kenya. A lifting of pandemic-related restrictions that disproportionately affected freedom of assembly and freedom of movement also produced positive change, as did a renewed commitment to judicial independence in some countries.

In addition to these outright improvements, the year brought fresh evidence of the limits of authoritarian power. Authoritarian influence at the United Nations and other international organizations faltered as democracies reaffirmed the value of multilateral engagement. Ukrainians, with material support from many democracies, beat back a vast Russian army that was hampered by decades of corruption. In China, the ruling Communist Party’s onerous and politicized COVID-19 policies were abruptly dismantled in the face of public protests.

The 2023 edition of Freedom in the World is the 50th in this series of annual comparative reports. As such, it provides an opportunity to reflect on the challenges to and achievements of democracy over the past five decades. Among the more significant challenges has been a widespread assault on the civil liberties that can be used to hold governments to account—most notably, freedom of expression.

Over the last 17 years, the number of countries and territories that receive a score of 0 out of 4 on the report’s media freedom indicator has ballooned from 14 to 33. The year 2022 brought more of the same, with media freedom coming under pressure in at least 157 countries and territories. Scores for a related indicator pertaining to freedom of personal expression have also suffered over the years amid greater invasions of privacy, harassment and intimidation, and incentives to self-censor both online and offline.

It has become more difficult to consolidate nascent democratic institutions in recent decades. More and more countries have remained Partly Free instead of moving toward full democratization. Still, the world is significantly freer today than it was 50 years ago. In 1973, 44 of 148 countries were rated Free. Today, 84 of 195 countries have earned that status. Many strong democracies that emerged during periods of progress have since withstood serious political, social, and economic pressures.

Ongoing protests against repression in Iran, Cuba, China, and other authoritarian countries suggest that people’s desire for freedom is enduring, and that no setback should be regarded as permanent. Democratic societies’ international solidarity, commitment to shared values, and continued support for human rights defenders are crucial to ensuring that the next 50 years bring the world closer to a state of freedom for all.

Direct attacks on democracy and the human cost of authoritarian rule

Dramatic declines in political rights and civil liberties during 2022 were driven by direct assaults on democratic institutions, whether by foreign military forces or incumbent officials in positions of trust. War, coups d’état, and power grabs repeatedly posed an existential threat to elected governments around the world.

In February, Ukrainians were violently thrust into the heart of the global struggle to defend democracy against authoritarianism. President Vladimir Putin of Russia, having already overseen the illegal occupation of Ukrainian territory in Crimea and eastern Donbas since 2014, launched a full-scale invasion of the country. Whatever false justifications for this war of aggression have been promulgated by the Kremlin’s state-controlled media, its clear purpose is to remove the elected leadership in Kyiv and deprive Ukrainians of their fundamental right to free self-government.

The war has been, as Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy put it, a disaster with a high price. In his desire to destroy democracy in Ukraine and deny Ukrainians their political rights and civil liberties, Putin has caused the deaths and injuries of thousands of Ukrainian civilians as well as soldiers on both sides, the destruction of crucial infrastructure, the displacement of millions of people from their homes, a proliferation of torture and sexual violence, and the intensification of already harsh repression within Russia.

Military coups

While the assault on Ukraine’s democracy came from a neighboring state, a growing number of countries faced attacks from within. Burkina Faso experienced the steepest decline in freedom in this year’s report, losing a total of 23 points on the 100-point scale and falling from Partly Free to Not Free status as a result of two successive coups. In January 2022, Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, leading a self-proclaimed Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration, ousted the elected president, suspended the constitution, dissolved the legislature, and instituted a curfew. Just eight months later, he was replaced by another officer, Captain Ibrahim Traoré, who dismissed the transitional government, again suspended the constitution, closed the borders, and issued orders that prevented civil society organizations from operating. Both coup leaders ruled by decree and made only vague commitments to holding democratic elections in the future.

Events at the end of 2022 showed that even unsuccessful coup attempts can do immediate harm to the political system and human rights, especially when they take place in a country that has previously experienced authoritarianism. In December, Peru’s President Pedro Castillo tried to avoid imminent impeachment by suspending Congress and declaring a nationwide curfew. Castillo’s attempted “autogolpe,” or self-coup, happened 30 years after President Alberto Fujimori seized legislative and judicial powers in the country with help from the military and began a decade-long dictatorship. Even though Castillo was quickly removed from office and replaced by the vice president, his arrest sparked large protests across the country and triggered the implementation of a state of emergency that granted special powers to security services and limited the right to assembly. Over two dozen people were killed and hundreds were injured in December alone as police responded to the protests with deadly force, and unrest continued into the new year. The crisis caused the country to drop from Free to Partly Free status and threatened to further undermine a political system that has endured multiple presidential resignations and impeachments in recent years.

In addition to the dangers they pose in the moment, coups and coup attempts can have repercussions that substantially degrade protections for human rights in the long run. Thailand’s civil society continues to feel the effects of a 2014 coup by army chief Prayuth Chan-ocha. Perceived critics of the military-backed government face charges under lèse-majesté laws, which forbid insulting the monarchy, and human rights organizations were subjected to increasingly intense legal harassment in 2022. The ruling junta in Guinea, which came to power in a 2021 coup, has continued to roll back rights and reverse the democratic gains of the past decade, banning all political protests last year. Since a 2021 coup in Myanmar, the military junta there has waged a relentless and brutal campaign of violence across the country, detaining and killing thousands of people, displacing approximately one million residents, and destroying an experiment with elected civilian rule that the military itself had initiated with a new constitution in 2008.

In Turkey, a failed 2016 coup attempt has cast a long shadow over political rights and civil liberties. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) used the incident to justify the removal of key democratic checks and balances and the elimination of political rivals. This process continued in 2022, as Turkey prepared for a pivotal presidential election in the first half of 2023. Ahead of the vote, the government adopted a new law to control the selection of judges who will review challenges to election results, and approved a “disinformation” law that could further stifle opposition campaigns and independent media.

The threat from incumbent leaders

Democratic institutions suffered from abuses by powerful incumbents in 2022. After assuming office through elections, these leaders rejected the established democratic process and sought to rewrite the rules of the game to maintain their grip on power.

Tunisia experienced the third-largest score decline of any country as a direct result of the actions of the elected president. Kaïs Saïed, who had unilaterally dismissed the prime minister and suspended the parliament in 2021, continued to consolidate power by formally dissolving the parliament in March. He then rolled out a new constitution that gave more authority to the presidency and dismantled legislative and judicial checks on the executive branch, securing approval for the document through a flawed referendum. December parliamentary elections, which were boycotted by most opposition parties, drew a voter turnout of just 11 percent and prompted calls from the opposition for Saïed to resign.

In El Salvador, the parliamentary supermajority gained by President Nayib Bukele’s allies in 2021 elections continued to help him undermine democratic controls. In March 2022, the legislature approved his request for a state of exception intended to address gang violence, which has led to the indefinite detention of tens of thousands of people, with little regard for their due process rights. Under the state of exception, authorities have also suspended anticorruption mechanisms that would shed light on government spending and contracts. In September, Bukele announced that he would compete for a second term, a year after the Constitutional Court—newly packed with his appointees after a wholesale purge—overturned a ban on consecutive presidential terms.

The victory of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party in Hungary’s April 2022 elections was facilitated by his government’s campaign since 2010 to systematically undermine the independence of the judiciary, opposition groups, the media, and nongovernmental organizations. Among other advantages, Fidesz benefited from legislative changes it had pushed through two years earlier, which raised the vote threshold that parties must reach to enter the parliament.

Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s warnings that he would not accept election results if he lost stoked mistrust in the democratic process among his supporters. After losing to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in a runoff, Bolsonaro avoided formally conceding, and his campaign later attempted to overturn the result in court by claiming that a computer error had disqualified large batches of votes. Just before Lula’s January 1 inauguration, Bolsonaro traveled to the United States, avoiding participation in the traditional transfer of the presidential sash to the new leader. The next week, thousands of the former president’s loyalists, who had repeatedly called for a military coup against the new government, stormed Congress, the Supreme Court, and the presidential palace. Although the elected administration retained power and cracked down on the perpetrators, Brazilian democracy remained on the defensive after this destructive event.

The worst excesses of unchecked power

When assessing the stakes of the struggle for democracy, it is important to remember the devastating costs that authoritarian rule can impose on entire populations. In the absence of any meaningful constraints on political power and the use of force, a growing number of regimes around the world have engaged in wholesale persecution of women or ethnic minority groups, in some cases drawing accusations of genocide.

Since overthrowing Afghanistan’s elected government in 2021, the Taliban have presided over a catastrophic economic collapse, a surge in hunger and poverty, and mass emigration. Rather than taking steps that would reduce its international isolation, however, the regime has moved in the opposite direction. The Taliban authorities barred girls from attending secondary school in March 2022, effectively ending education for women after the sixth grade, and in December they ordered private and public universities to prohibit female students from attending classes, preventing women who already reached higher education from completing their studies. Also in December, authorities issued a decree banning women from working in national and international nongovernmental organizations. Lacking any recourse within the political system, Afghan women took their demands to the streets, where they were met with water cannons, beatings, and arrests.

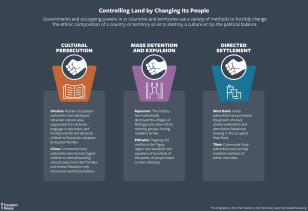

The number of countries and territories where the government or an occupying power is deliberately changing the ethnic composition of the population in order to destroy a culture or tip the political balance increased from 19 to 21 last year. Ethiopia and Ukraine were added to the list, joining longtime sites of forced ethnic change like China and Myanmar.

In Ethiopia, the ongoing civil conflict centered on the northern Tigray region has resulted in, among other abuses, extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of people from their homes on the basis of their ethnicity. Like other countries and territories in the Not Free category, Ethiopia lacks many aspects of the rule of law that might protect its citizens’ fundamental human rights.

Moscow’s occupation of Crimea and eastern Donbas has entailed a long-standing campaign of forced ethnic change in those Ukrainian territories. Since 2014, many Crimean Tatars and ethnic Ukrainians have left the regions, driven not only by political persecution and the violence of war but also by overt policies of Russification, including encouragement of migration from Russia, transfers of local prisoners and conscripts to Russia, deportations of those who refuse Russian citizenship, and repression of the Ukrainian and Tatar cultures and languages within the education system. These practices were expanded to other parts of occupied Ukraine after the full-scale invasion, and augmented with horrific projects like the mass abduction and removal of Ukrainian children to Russia.

Forced ethnic change is also a matter of official policy for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which aims to deliberately break up the cultures and geographic concentrations of ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia. Among the 57 Not Free countries in the world, China ranks near the absolute bottom in terms of overall political rights and civil liberties. It is joined there by Myanmar, where the military has engaged in violent attacks on and expulsions of the Rohingya population as well as several other ethnic groups.

A possible turning point for global freedom

There were signs during the past year that the world’s long freedom recession may be bottoming out, which would set the stage for a future recovery. The gap between the number of countries that registered overall improvements in political rights and civil liberties and those that registered overall declines in 2022 was the narrowest it has ever been through 17 consecutive years of deterioration. The number of countries with declines, at 35, was the smallest recorded since the negative pattern began. Thirty-four countries registered improvements.

The gains came in various forms. Eight countries registered modest improvements in civil liberties due to the rollback of COVID-19 restrictions that had disproportionately infringed on the freedoms of assembly and movement. But the most significant positive developments were driven by competitive elections in Latin America and Africa, with politicians and ordinary people in the affected countries reaffirming their commitment to the democratic process.

The year also brought fresh evidence of the limits of authoritarian power, as key regimes faltered in their attempts to exert influence at international organizations and their internal governance flaws led to dramatic policy setbacks.

Consolidating democracy through elections

Two countries, Lesotho and Colombia, improved from Partly Free to Free last year following successful competitive elections. In Lesotho, Sam Matekane’s Revolution for Prosperity party won a plurality of seats in the parliament and replaced the incumbent government. Representing a departure from years of instability, the elections were hailed as fair and peaceful by observers from numerous international organizations. In Colombia, a broad coalition enabled Gustavo Petro to win the June presidential runoff vote, overcoming political forces associated with former president Álvaro Uribe, who has dominated the political scene since the early 2000s. The country had been making gains in respect for fundamental rights even before the election period, as the government granted temporary protection permits to more Venezuelan refugees and the Constitutional Court decriminalized abortion.

Establishing a strong record of peaceful political competition and democratic power transfers can be a long and arduous process. The elections in both Colombia and Lesotho were not without problems, and obstacles to further progress remain. Lesotho continues to struggle with ills including police brutality, a legacy of political influence exercised by the security agencies, and chronic political turmoil. In Colombia, politicians faced threats of violence while on the campaign trail, and illegal armed groups associated with the far left and far right remain a menace to the rule of law and civil society. The country is one of the deadliest in the world for human rights defenders.

The United States navigated its 2022 midterm elections without any violence of the sort that occurred during the January 2021 assault on the Capitol. The elections produced a divided Congress, with the Republican Party winning a narrow majority in the House of Representatives while the Democratic Party maintained control in the Senate. Although hundreds of Republican candidates who explicitly denied the legitimacy of President Joseph Biden’s victory over former president Donald Trump in the 2020 election ran for office across the country, they lost in almost all key statewide races. This comparative stability on the political front was offset by the Supreme Court’s removal of constitutional protections against strict abortion bans.

In Slovenia, a competitive election with the highest voter turnout in 20 years resulted in defeat for the right-wing populist government, which had repeatedly threatened media freedom and other democratic norms. Kenya held what observers hailed as its most transparent presidential election ever, and the results were confirmed by an independent Supreme Court. The country’s political leaders notably refrained from the boycotts and incitement of ethnic violence that had disrupted some previous elections.

Checks on autocrats’ international influence

Authoritarian powers have made an effort to reshape the international system by exercising their influence at the United Nations. They have embraced UN participation and multilateralism primarily as a means of defending themselves against international mechanisms aimed at transparency and accountability. Elected five times to the UN Human Rights Council, the Chinese government has repeatedly blocked resolutions addressing its own policies. It has also joined with its counterparts from Iran, Belarus, North Korea, Cuba, and other member states in the so-called Group of Friends in Defense of the Charter of the United Nations to criticize the use of sanctions.

Regional organizations too have been used to prop up autocrats. The Russian-controlled Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), for example, deployed troops in January 2022 to protect Kazakhstan’s President Kasym-Zhomart Tokayev from large-scale antigovernment protests sparked by a sharp rise in fuel prices.

However, authoritarian cooperation is motivated by narrow self-interest and centers on low-cost actions, meaning it can fracture when regimes’ priorities diverge or they encounter determined democratic pressure. The CSTO’s response to the crisis in Kazakhstan, for instance, stood in stark contrast to the organization’s failure to assist Armenia, the only member state that is rated Partly Free, as it suffered repeated attacks on its sovereign territory by Azerbaijan.

Few of Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian allies have openly supported his war of aggression against Ukraine. CCP leader Xi Jinping has not endorsed the invasion or provided military support despite describing the bilateral partnership as having “no limits” early in 2022. The countries of the Caucasus and Central Asia are often seen as lying within Moscow’s geopolitical orbit, but Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan have declined to recognize Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territory, and they have all complied with sanctions against Russian banks. The Kremlin’s most steadfast ally in the region continues to be President Alyaksandr Lukashenka of Belarus, who is dependent on Russian support to maintain his own tenuous grip on power.

Meanwhile, democracies are standing up for human rights at international organizations. After years of being shielded by diplomats from Russia and China, Myanmar’s junta was condemned by the UN Security Council in December for using violent tactics against prodemocracy activists. Similarly, despite the presence of authoritarian member states, the UN Human Rights Council voted to suspend Russia in April. In October, the council went further, appointing a special rapporteur to monitor the human rights situation in Russia by a vote of 17 to 6.

Venezuela was denied a seat on the UN Human Rights Council in October elections by the General Assembly. While most regional groups did not nominate more candidate countries than available seats, democratic Costa Rica and Chile both ran to block Venezuela’s bid for a seat from the Latin America and Caribbean group. In December, Iran was removed from the UN Commission on the Status of Women and prevented from serving the rest of its four-year term as a result of a resolution introduced by the United States and supported by 28 other countries. The measure noted that the Iranian government’s campaign to suppress the rights of women and girls by using force against protesters flew in the face of the UN body’s mission to promote gender equality.

The contest between democratic and authoritarian norms at international organizations is far from over. But the positive developments of the past year should encourage even more active democratic engagement in multilateral forums.

(Image credit: Reuters/Thomas Peter)

Control over competence

Autocrats’ behavior at the international level is a reflection of their governing methods at home, where in the absence of a genuine popular mandate, they rely on a crude combination of corruption and force to maintain control. The democratic institutions that might moderate graft and state violence—such as opposition parties, independent courts, a free press, and civil society groups—are suppressed as potential threats to the leader’s power. When such corrosive problems are allowed to go unchecked, they can undermine the regime’s own goals and threaten the lives of ordinary people.

Corruption comes at a high cost to both public services and government revenue. In Venezuela, endemic corruption orchestrated by the regime of Nicolás Maduro has stripped the land of natural resources and undermined crucial infrastructure, impoverishing the population and impeding the government’s ability to address health and economic emergencies. The country consequently faces an ongoing humanitarian crisis, with shortages of electricity, medicine, and food. Over seven million people have fled abroad.

In Russia, Putin’s long history of enabling corruption at the highest levels has left him unable to fulfill the goals of his war of aggression. Despite the fact that the Kremlin spent hundreds of billions of dollars on modernizing the Russian military over the last two decades, it remains a poorly equipped force, with soldiers who lack food and basic medical supplies and use Soviet-era maps and weapons. Many in the United States and elsewhere believed Putin’s boasts that Russian military capabilities matched those of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and far outmatched those of Ukraine, but the progress of the war quickly disproved those claims. The families of Russian conscripts are now being asked to provide them with everything from body armor to gauze for bandages. None of this has stopped the Kremlin from sending such soldiers to their deaths as the war grinds on, since admitting defeat would threaten the illusion of strength and shrewdness on which Putin’s illegitimate authority partly depends.

As with corruption, the need to maintain control through overwhelming force—and the lack of mechanisms to moderate it—can interfere with an autocrat’s ability to adjust policy in response to public frustrations. China’s disastrous experience with the CCP’s “zero COVID” policy illustrated what can happen to people caught in an authoritarian system that is more focused on compelling their obedience than ensuring their well-being.

President Xi, who has been in power since 2012 and secured a third term as CCP leader in October 2022, has repeatedly claimed that China’s political system is superior to democracy in providing stability, prosperity, and even protection from the spread of COVID-19. In dealing with the health threat, CCP officials leaned on existing tools of repression, expanded the use of surveillance technologies, and imposed mass quarantines on whole cities that disproportionately restricted freedom of movement and often threatened access to food and medical care. In December 2022, the CCP abruptly abandoned zero-COVID restrictions without adequate preparation. At the end of the month, reports emerged of overwhelmed hospitals and as many as 1 million new infections per day.

The about-face was triggered in part by nationwide protests that followed a deadly residential fire in Urumqi in late November, in which both victims and rescuers were reportedly hampered by COVID-related restrictions on movement. As Freedom House’s China Dissent Monitor has shown, protests in China on a variety of issues are not uncommon. Despite the likelihood of grave punishments, citizens participated in 638 demonstrations and similar dissent events between June and September 2022. The zero-COVID protests in the wake of the Urumqi blaze were preceded by other acts of defiance, including the “bridge man” protest against the central government in Beijing in October. But even in the face of clear public outrage on a national scale, the CCP remains unable to address people’s underlying grievances. It failed to make health restrictions more tailored or humane, or to lift them with appropriate caution. Indeed the party provoked further anger by promoting officials who were responsible for some of the greatest suffering, including Li Qiang, who had overseen harsh lockdowns as party chief in Shanghai.

The policy blunders committed by Moscow and Beijing demonstrate that the fallibility of authoritarian governments, and not just their malice, can take an incredibly large toll on human life. Corruption, criminality, and feckless leadership have made the Russian army far more deadly to soldiers and civilians on both sides of the front line, despite the force’s failure to achieve stated war aims. Similarly, the Chinese government’s botched reversal of its procrustean COVID-19 policies may prove even more destructive than the years of brutal lockdowns themselves. Authoritarian shortcomings must be assessed with clear eyes. These regimes are unlikely to govern more effectively than democracies, but their errors are part of what makes them so dangerous.

Explore 50 Years of Freedom in the World

Five decades of country-by-country analysis in Freedom in the World has confirmed a remarkable fact: once countries earn the designation of Free, they tend to keep it. Explore the fifty year Freedom in the World timeline that highlights some of the milestones in the fight for freedom over the past 50 years.

Free expression: A leading indicator of democratic decline

F reedom of expression, a fundamental component of democracy, has been under sustained attack around the world for the last 17 years. Of all the indicators that Freedom in the World uses to assess political rights and civil liberties, freedom of the media and freedom of personal expression have declined the most precipitously since 2005. This assault coincided with the rapid uptake of information and communication technologies that have effectively broken many states’ media monopolies. In too many places, however, authorities responded to new forms of online expression with harsh offline punishments and technological innovations of their own.

Press freedom in retreat

Freedom for independent journalism has plummeted. The number of countries and territories that have a score of 0 out of 4 on the media freedom indicator has ballooned from 14 to 33 during the 17 years of global democratic decline, as journalists faced persistent attacks from autocrats and their supporters while receiving inadequate protection from intimidation and violence even in some democracies. The past year brought more of the same, with media freedom coming under pressure in at least 157 countries and territories assessed by Freedom in the World .

In Russia, a multiyear media crackdown went into overdrive as the government sought to eliminate domestic opposition to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Russian independent journalists and outlets had long contended with laws that labeled them as foreign agents, extremists, or “undesirable.” In 2022, the expansion of criminal laws targeting the spread of false information related to the war empowered Roskomnadzor, the federal media and telecommunications regulator, to block websites more aggressively without a court order. Authorities blocked access to most of the independent media outlets that were still available in the country, including Ekho Moskvy, Dozhd, Voice of America, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), and Meduza. Some foreign journalists were also denied entry to Russia.

The number of countries and territories that have a score of 0 out of 4 on the media freedom indicator has ballooned from 14 to 33 during the 17 years of global democratic decline.

Moscow’s tactics have spread to Central Asia, where Kyrgyzstan has adopted many similar laws targeting the media. Kyrgyz authorities recently tried and failed to convict a prominent investigative journalist, Bolot Temirov, on dubious charges of forgery. In an outrageous violation of the rule of law, Temirov was summarily stripped of his citizenship and transported to Russia in late November 2022, despite the fact that he had been born in Kyrgyzstan.

Journalists routinely face harassment and threats in reprisal for their efforts to expose corruption. Two reporters, including a Cable News Network (CNN) correspondent, fled Guatemala last year after they received explicit threats, while another was arrested by the government in July. José Rubén Zamora, director of the newspaper El Periódico , which has faced severe harassment in the past, was charged with financial crimes in what many observers describe as a bid to censor an outlet that has reported critically on the government of President Alejandro Giammattei. Zamora remained in pretrial detention through the end of the year, with the trial reportedly not scheduled to start until May 2023.

Authorities in a variety of countries failed to offer effective protections to media professionals who were at risk of extralegal violence from nonstate actors. Journalists reporting on the security situation in Haiti, which had worsened since the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, experienced an extraordinary amount of physical violence in 2022. Members of the media were executed by gangs, killed while in police custody, and shot at while on their way to work.

The risks of personal expression

Beyond the news media, ordinary people are less free to express their views to others, whether online or off. Many governments have been quick to reapply existing repressive laws to the online sphere and adopt invasive technologies to monitor digital communication. Others continue to resort to old-fashioned methods of control over speech, like the use of human informants and physical searches. The result is a pervasive sense of fear among civic activists, members of marginalized communities, and average citizens when discussing sensitive topics in public, semipublic, or private settings.

From 2005 to 2022, the number of countries and territories that scored a 0 out of 4 on this indicator rose from six to 15, signaling a nearly complete lack of freedom to voice antigovernment opinions even in private. In Nicaragua, years of worsening crackdowns on opposition to the regime of President Daniel Ortega culminated in show trials of dozens of people—accused of crimes ranging from treason to spreading false news and undermining national integrity—based almost solely on evidence that they made critical remarks about the government. Such cases clearly discourage others from speaking out. Conditions are at least as grim in Afghanistan, Belarus, Russian-occupied eastern Donbas, and Eritrea, where authorities have deployed networks of informants and checked people’s phones to suppress the sharing of dissenting opinions.

The penalties for nonviolent criticism can be extreme. Myanmar’s military junta executed prodemocracy activist Kyaw Min Yu, better known as Ko Jimmy, for speaking out against the 2021 military coup that displaced an elected civilian government. In August 2022, a terrorism court in Saudi Arabia sentenced Nourah bint Saeed al-Qahtani to 45 years in prison merely for social media posts, just weeks after handing a 34-year sentence to another woman, Salma al-Shehab, for sharing posts by Saudi dissidents. In Hong Kong, following Beijing’s imposition of the draconian National Security Law in 2020, authorities began pursuing national security and sedition charges against both political activists and ordinary residents for expressing dissent, for example by playing protest songs, clapping in court, or putting up posters.

There are fewer and fewer spaces where people can express themselves without fear of surveillance. At a time when the internet has become fundamental to people’s daily lives, virtually all online activities generate data that are subject to monitoring by authorities, whether directly or through commercial systems and advertising technology that can be exploited to reveal sensitive information. Many countries employ police units to search social media posts for banned forms of political, artistic, religious, or sexual expression. Networks of street cameras equipped with artificial intelligence can identify protesters and track their whereabouts. And the proliferation of spyware has made electronic surveillance potentially ubiquitous; even the presence of an internet-connected device can be enough to deter uninhibited discussion.

No country can match the scale and sophistication of China’s surveillance state, in which residents’ activities are invasively monitored by public security cameras, urban grid managers, and automated systems that detect suspicious and banned behavior, including innocuous expressions of ethnic and religious identity. Workers at private digital platforms in China are required to censor an ever-changing list of prohibited terms and to notify authorities about users who dare to criticize the CCP. Those identified as dissidents can face consequences including forced disappearance and torture.

But surveillance has also chilled freedom of expression in countries rated Free and Partly Free. Technology companies are generally required to maintain a log of their users’ online activities, and in many countries, they must share it with authorities through a process that lacks judicial oversight and guardrails against abuse. The growing and unregulated global market for commercial spyware has enabled infringements on the right to private expression that often stretch across international borders. Rather than collecting data or intercepting traffic at fixed points in the telecommunications infrastructure, spyware targets a victim’s smartphone or other electronic device regardless of its location, and allows the capture of phone records, contact lists, geolocation data, keyboard strokes, and even camera and microphone inputs. The Pegasus spyware product has been found on devices in France, Hungary, India, Israel, Mexico, and Poland. Victims included journalists and politicians, while the perpetrators remained unknown and unaccountable for their abuses.

These pernicious encroachments on freedom of expression pose an obvious threat to democracy. While professional journalists and media outlets disseminate information, ensure transparency, and hold the powerful to account, the freedom of personal expression reinforces individual autonomy and facilitates discussion of differing opinions. It is also crucial to fostering associations and communities within a larger society, including those based on ethnic, cultural, sexual, gender, and religious identities. The denial of press freedom and freedom of personal expression bolsters authoritarian control by cutting citizens off from accurate information and, just as importantly, from one another.

Lessons from 50 years of Freedom in the World

Over the past five decades, people in every region of the world have demanded and built democracies even under extremely difficult circumstances. Once fully established, most democratic systems have stood strong against a wide array of challenges.

In 1973, when Freedom House published its first comprehensive assessment of political rights and civil liberties, only 44 of 148 countries were classified as Free. Today, 84 of 195 countries are Free. The varied paths that these countries followed show there is no single method for improving or protecting political rights and civil liberties. However, popular self-government through credible, competitive, free, and fair elections continues to be the hallmark of democracy and a guarantee of its associated benefits.

A record of progress

The first editions of Freedom in the World coincided with the beginning of the “third wave” of democratization, when many military dictatorships were giving way to elected civilian leaders. A military junta in Greece collapsed in 1974 amid a confrontation with Turkey over control of Cyprus. Greek democracy was restored through general elections that were held just 142 days after the beginning of the crisis.

After right-wing dictator Francisco Franco died in 1975, Spain began its own transition to democracy, which took years and required overcoming the commitment of the armed forces to the old regime. The transition was confirmed through a free general election in 1977 and the adoption of a new constitution the following year. Spain’s democracy proved resilient in the early 1980s, when the government survived a coup attempt and a second general election resulted in a peaceful transfer of power to the socialist opposition.

Positive change followed in Latin America. After a disastrous invasion of the Falkland Islands in 1982, the military leaders who had presided over Argentina’s “dirty war”—a bloody campaign of state terrorism against political dissidents—finally stepped down, allowing for a general election that returned the country to civilian rule. Democracy also returned to Brazil after the military, which had begun to oversee gradual political liberalization, lost control in the 1985 elections. A military regime that caused Uruguay to be called “the torture chamber of Latin America” faltered after a failed attempt to reform the constitution in 1980, and ended with elections four years later. Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship in Chile also came to an end through the power of the ballot box when referendum voters rejected a proposal to give the general eight more years in office.

In the 1990s, Taiwan cemented a status of Free after holding its first direct presidential election, having previously ended 38 years of martial law in 1988 and instituted full multiparty legislative elections a few years later. In 1992, South Korea elected its first civilian president since 1961. South Africa, which was rated Free for the first time in the 1994–95 edition of Freedom in the World , broke from a violent and entrenched system of racist hierarchy in order to create the conditions for an inclusive, free, and fair election. The balloting resulted in the elevation of Nelson Mandela to the presidency and the formation of a new government of national unity.

The fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 and of the Soviet Union itself in 1991 eventually brought freedom to a host of Central and Eastern European states, many of which sought closer ties to their fellow democracies in Western Europe. In 2004 alone, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia all joined the European Union, with Romania and Bulgaria following in 2007.

Despite pressure from illiberal forces since the mid-2000s, the gains of the third wave of democratization have mostly held. Consolidated democracies, where political rights and civil liberties have been secured, continue to endure in a dangerous world.

Setbacks and slowdowns

The 50 years of data generated by Freedom in the World offer heartening proof that democratic progress is always possible. Forty countries that exist today have always had the status of Free in the report, while only 12 countries that exist today have always been Not Free. Whereas Free countries tend to stay Free for decades, Not Free and Partly Free countries are less static, often experiencing waves of liberalization or repression that move them from one category to another.

However, the possibility of progress does not make it inevitable. The overall decline in global freedom over the last two decades has created a more hostile environment for individual countries’ democratization efforts and provided transnational support for illiberal leaders. Freedom in the World data show that consolidating and protecting nascent democratic institutions has become more difficult than in the heyday of democratization following the end of the Cold War. More and more countries are remaining Partly Free instead of continuing their march to Free status. Worryingly, some Free countries are losing ground, including India, which was downgraded to Partly Free two years ago, and Peru, which was downgraded in this edition after its latest, one-year stint in the Free category.

Democratization has also failed to take hold in certain clusters of countries. Most of the states that emerged from the collapse of the Soviet Union remain dominated by strongmen who transformed Soviet-era connections into kleptocratic networks, which have enriched their members while impoverishing ordinary citizens. These corrupt authoritarian regimes have also fomented instability and threatened democracies across the region. In addition to Moscow’s war against Ukraine, other recent conflicts include border clashes between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan and the growing incursions by Azerbaijani forces into Armenia.

Popular self-government through credible, competitive, free, and fair elections continues to be the hallmark of democracy and a guarantee of its associated benefits.

The Arab Spring uprisings of 2011, which began by driving out Tunisian dictator Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali and sparked new hope for democratization in North Africa and the Middle East, ended in disappointment. Monarchs in Jordan and Morocco approved modest or illusory constitutional reforms in a bid to defuse popular discontent with their rule, while the hereditary rulers of the wealthy Persian Gulf region moved to stamp out any embers of dissent at home and assist authoritarian partners elsewhere. Security forces cracked down on prodemocracy protesters in Libya, Syria, and Yemen, and the ensuing violence devolved into civil wars that were made even more chaotic by multiple foreign interventions. Two years after the revolution in Egypt, the military removed the elected president through a coup, and instituted a new and even more repressive authoritarian regime.

In Africa, countries such as Burundi, the Republic of the Congo, Zimbabwe, and Uganda showed promise at times but later saw their status improvements reversed, while more recent backsliding in Benin and Senegal led both to drop from Free to Partly Free status. Mali, which had been rated Free since 1995, was rocked by a military coup and rebel insurgencies in 2012 that pulled it down to Not Free.

The imperative of solidarity

Democracies must maintain external pressure on authoritarian regimes and make sure that in maneuvering to thwart one dictator’s acts of aggression, they do not cultivate partnerships with other despots or downplay human rights principles in their foreign policies. International solidarity and support will remain vital to the expansion of political rights and civil liberties worldwide.

Advocacy for human rights norms must also be paired with support for the key proponents of democratic values within their respective countries: human rights defenders. Today, in every region of the world, people striving to build more democratic societies and expand the exercise of fundamental freedoms are instead being subjected to arbitrary detention and sentenced to lengthy terms in prison, where they often experience torture and other cruel or degrading treatment.

Supporting the work of human rights defenders is essential for the promotion of freedom in both open and closed political spaces. Human rights defenders are agents of change. In 2022, for instance, the Indonesian parliament passed a law against sexual violence after a years-long advocacy campaign by civil society groups. The previous year, women’s rights activists in El Salvador secured a favorable ruling at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights against the country’s broad ban on abortion.

Human rights defenders are sometimes the only ones in their countries with the will and capacity to protect others against severe abuses, expose official wrongdoing, and alert the rest of the world to acts of repression, often at considerable risk to their safety. Activists in Cameroon have received death threats for documenting human rights violations amid a conflict between security forces and separatists in the country’s Anglophone regions. An activist and journalist in Vietnam who helped to expose the disastrous impact of a 2016 chemical spill was sentenced to seven years in prison the following year. In addition to facing intimidation, legal censure, harassment, and physical assaults, hundreds of rights defenders are killed every year.

Democratic governments must recommit not only to standing up for these activists in their public statements and diplomacy, but also to providing concrete support and protection in the form of emergency assistance, capacity-building programs, and democracy shelters. Though unarmed, human rights defenders are on the front lines of the global struggle for freedom. They should never be treated as if the struggle is theirs alone.

The desire for freedom

More than anything else, five decades of Freedom in the World reports demonstrate that the demand for freedom is universal. The years have shown that popular challenges to authoritarian rule are a recurring theme in even the most repressive societies.

Tanks smashed the prodemocracy movement that made its stand in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989, and the CCP’s fear of renewed calls for freedom has motivated escalating campaigns of repression against targets including mainland dissidents, ethnic and religious minority populations, and the people of Hong Kong. But Beijing’s rejection of direct executive elections in Hong Kong in 2014 led to a series of massive protests that signaled abiding public support for universal suffrage. And despite crackdowns on demonstrations large and small, protests of all types continue across the mainland.

Cuba, with its long history of repression and international isolation, has been shaken by growing resistance to the regime. Demonstrations in July 2021 that drew attention to a dearth of fundamental freedoms and serious economic problems marked the largest antigovernment mobilization since the Maleconazo protests of 1994, which were sparked by police blocking Cubans from fleeing the country by boat. In both cases, security forces responded violently, yet outbreaks of dissent continue. People took to the streets again in 2022 to protest mismanaged infrastructure in the wake of hurricane-related blackouts.

Recent events in Iran are another reminder that millions of people are willing to call for democracy and defend their rights even at great personal risk. The current regime itself took power after popular protests brought down the monarchy in 1979, and Iranians have repeatedly voiced their objections over the years as it descended deeper into dictatorship. In 2009, shortly before the Arab Spring, citizens protested for the better part of a year in what came to be known as the Green Movement, after a fraudulent election handed victory to incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Conditions have worsened since then, with authorities using lethal violence to put down successive waves of protests. In 2022, fresh demonstrations were sparked by the death in custody of Jina Mahsa Amini, a young woman arrested by the morality police. The movement spread to more than 80 cities and was viciously opposed by the government, resulting in hundreds of deaths on the streets, thousands of arrests, and a growing number of summary executions.

Reflecting on the 1979 Iranian Revolution, Raymond Gastil wrote in the 1980 edition of the Freedom in the World report: “Iran will remain for generations a difficult land in which to institutionalize democracy. Yet I suggest Iranians will repeatedly try, that they will be unsatisfied with anything else.… If the Revolution establishes a new tyranny, these people will soon feel cheated and strive again for freedom.” This prediction has certainly proven true for Iranians, and the same could be said for people everywhere. So long as human beings remain true to their natural yearning for liberty, authoritarians will never be secure, and the global movement for democracy will never be defeated.

Test Your Knowledge!

The 50th edition of Freedom in the World is now live! Test your knowledge of some of the key findings from our 2023 report by taking our quiz.

Explore the Report

Countries in Detail

Visit our Countries in Detail page to view all Freedom in the World 2023 scores and read individual country narratives.

Regional Trends & Countries in the Spotlight

Visit our Regional Trends & Countries in the Spotlight page to learn about regional trends and status changes, and to access Freedom in the World 2023 data.

Policy Recommendations

Democracies and private sector actors should work to support core democratic principles and basic human rights at home and around the world.

Report Materials

Download Report PDF

- Full Report PDF

- Abridged PDF (Coming Soon)

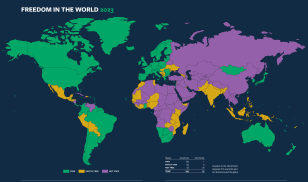

Report Map

Explore the interactive Freedom in the World 2023 map here , where you can see country scores, Freedom Status, and trends. Download the printable static map .

About the Report

Freedom in the World is Freedom House’s flagship annual report, assessing the condition of political rights and civil liberties around the world. It is composed of numerical ratings and supporting descriptive texts for 195 countries and 15 territories. Freedom in the World has been published since 1973, allowing Freedom House to track global trends in freedom for 50 years.